Since the early 1990s, object-oriented programming (OOP) has been the dominant programming paradigm in industry and education, and nearly all widely used languages developed since then have inlcuded support for it. Go is no exception.

Methods

Although there is no universally accepted definition of object-oriented programming, for our purposes, an object is simply a value or variables that has methods, and a method is a function associated with a particular type. An object-oriented program is one that uses methods to express the properties and operations of each data structure so that clients need not access the object’s representation directly.

Method Declarations

A method is declared with variant of the ordinary function declaration in which an extra parameter appears before the function name. The parameter attachs the function to the type of that parameter.

package geometry

import "path"

type Point struct{ X, Y float64 }

// traditional funcitoni

func Distance(p, q Point) float64 {

return maht.Hypot(p.X-q.X, p.Y-q.Y)

}

// same thing, but as a method of the Point type

func (p Point) Distance(q Point) float64 {

return maht.Hypot(p.X-q.X, p.Y-q.Y)

}

The extra parameter p is called the method’s receiver, a legacy from early object-oriented languages that described calling a method as “sending a message to an object”.

In Go, we don’t use a special name like this or self for the receiver; we choose receiver names just as we would for any other parameter. Since the receiver name will be frequently used, it’s a good idea to choose something short and to be consistent across methods. A common choice is the first letter of the type name, like p for Point.

In a method call, the receiver argument appears before the method name. This parallels the declaration, in which the receiver parameter appears before the method name.

p := Point{1, 2}

q := Point{4, 6}

fmt.Println(Distance(p, q)) // "5", function call

fmt.Println(p.Distance(q)) // "5", method call

There’s no conflict between the two declarations of functions called Distance above. The first declares a package-level function called geometry.Distance. The second declares a method of the type Point, so its name is Point.Distance.

The expression p.Distance is called a selector, because it select the appropriate Distance method for the receiver p of type Point. Selectors are also used to select fields of struct types, as in p.X. Since methods and fields inhabit the same name space, declaring a method X on the struct Point would be ambiguous and the compiler will reject it.

Methods with a Pointer Receiver

Because calling a function makes a copy of each argument value, if a function needs to update a variable, of if an argument is so large that we wish to avoid copying it, we must pass the address of the variable using a pointer. The same goes for methods that need to update receiver variable: we attach them to the pointer type, such as *Point.

func (p *Point) ScaleBy(factor flaot64) {

p.X *= factor

p.Y *= factor

}

The name of this method is (*Point).ScaleBy. The parentheses are neccessary; without them, the expression would be parsed as *(Point.ScaleBy).

In a realistic program, convention dictates that if any method of Point has a pointer receiver, the all methods of Point should have a pointer receiver, even ones that don’t strictly need it.

Named types (Point) and pointers to them (*Point) are the only types that may appear in a receiver declaration. Furthermore, to avoid ambiguities, method declarations are not permitted on named types that are themselves pointer types:

type P *int

func (P) f() { /* ... */ } // compile error: invalid receiver type

If the receiver p is a variable of type Point but the method requires a *Point receiver, we can use this shorthand:

p.ScaleBy(2)

and the compiler will perform an implicity &p on the variable. This works only for variables, including struct field like p.X and array or slice elements like perim[0]. We cannot call a *Point method on a non-addressable Point receiver, because there’s no way to obtain the address of a temporary value.

// compile error: cannot call pointer method on Point literal

// compile error: cannot take the address of Point literal

Point{1, 2}.ScaleBy(2)

But we can call a Point method like Point.Distance with a *Point reciver, because there is a way to obtain the value from the address: just load the value pointed to by the receiver. The compiler inserts an implicit * operation for us. The two function call are equivalent:

Either the receiver argument has the same type as the receiver parameter, for example both have type T or both have type *T:

Point{1, 2}.Distance(q) // Point

pptr.Distance(q) // Point

If all the methods of a named type T have a receiver type of T itself (not *T), it is safe to copy instances of that type; calling any of its methods necessarily makes a copy. But if any method has a pointer receiver, you should avoid copying instances of T because doing so may violate internal invariants.

Nil Is a Valid Receiver Value

Just as some functions allow nil pointers as arguments, so do some methods for their receiver, especially if nil is a meaningful zero value of the type, as with maps and slices.

When you define a type whose methods allow nil as a receiver value, it’s worth pointing this out explicitly in its documentation comment.

Composing Types by Struct Embedding

import "image/color"

type Point struct{ X, Y float64 }

type ColoredPoint struct {

Point

Color color.RGBA

}

We could have defined ColoredPoint as a struct of three fields, but instead we embedded a Point to provide the X and Y fields. A similar mechanism applies to the methods of Point. We can call methods of the embedded Point field using a receiver of type ColoredPoint, even though ColoredPoint has no declared methods:

red := color.RGBA{255, 0, 0, 255}

blue := color.RGBA{0, 0, 255, 255}

var p = ColoredPoint{Point{1, 1}, red}

var q = ColoredPoint{Point{5, 4}, blue}

fmt.Println(p.Distance(q.Point)) // "5"

p.ScaleBy(2)

q.ScaleBy(2)

fmt.Println(p.Distance(q.Point)) // "10"

The methods of Point have been promoted to ColoredPoint.

Notice the calls to Distance above. Distance has a parameter of type Point, and q is not a Point, so although q does have an embedded field of that type, we must explicitly select it. Attempting to pass q would be an error:

p.Distance(q) // compile error: cannot use q (type ColoredPoint) as type Point in argument to p.Point.Distance

A ColoredPoint is not a Point, but it “has a” Point, and it has two additional methods Distance and ScaleBy promoted from Point. If you prefer to think in terms of implementation, the embedded field instructs the compiler to generate additional wrapper that delegate to the declared method, equivalent to these:

func (p ColoredPoint) Distance(q Point) float64 {

return p.Point.Distance(q)

}

func (p *ColoredPont) ScaleBy(factor float64) {

return p.Point.ScaleBy(factor)

}

When Point.Distance is called by the first of these wrapper methods, its receiver value is p.Point, not p, and there is no way for the method to access the ColoredPoint in which the Point is embedded.

A struct type may have more than one anonymous field. When the compiler resolves a selector such as p.ScaleBy to a method, it first looks for directly method named ScaleBy, then for methods promoted once from ColoredPoint’s embedded fields, then for methods promoted twich from embedded fileds within Point and RGBA, and so on. The compiler reports an error if the selector was ambiguous because two methods were promoted from the same rank.

With embedding, it’s possible and sometimes useful for unmamed struct types to have methods too. The following example shows part of a simple cache implemented using two package-level variable, a mutex and the map that it guards:

var (

mu sync.Mutex // guards mapping

mapping = make(map[string]string)

)

func Lookup(key string) string {

mu.Lock()

defer mu.Unlock()

return mapping[key]

}

The version below is funcitonally equivalent but groups together the two related variables in a single package-level variable, cache:

var cache = struct {

sync.Mutex

mapping map[string]string

}{

mapping: make(map[string]string),

}

func Lookup(key string) string {

cache.Lock()

defer cache.Unlock()

return mapping[key]

}

The new variable gives more expressive names to the variables related to the cache, and because the sync.Mutex field is embeed witin it, its Lock and Unlock methods are promoted to the unnamed type, allowing us to lock the cache with a self-explanatory syntax.

Method Values and Expressions

Usually we select and call a method in the same expression, as in p.Distance, but it’s possible to separate these two operations. The selector p.Distance yields a method value, a function that binds a method (Point.Distance) to a specific receiver value p. This function can then be invoked without a receiver value; it needs only the non-receiver arguments.

For example, the function time.AfterFunc calls a function value after a specified delay. This program uses it to launch the rocket r after 10 seconds:

type Rocket struct { /* ... */

}

func (r *Rocket) Launch() { /*...*/ }

r := new(Rocket)

time.AfterFunc(10*time.Second, func() { r.Launch() })

The method values syntax is shorter:

time.AfterFunc(10*time.Second, r.Launch)

Related to the method value is the method expression. When calling a method, as opposed to an ordinary function, we must supply the receiver in a special way using the selector syntax. A method expression, written T.f or (*T).f where T is a type, yield a function value with a regular first parameter taking the place of the receiver, so it can be called in the usual way.

In the following example, the variable op represents either the addition or the subtraction method of type Point, and the Path.TranslateBy calls it for each point in the Path:

type Point struct{ X, Y float64 }

func (p Point) Add(q Point) Point { return Point{p.X + q.X, p.Y + q.Y} }

func (p Point) Sub(q Point) Point { return Point{p.X - q.X, p.Y - q.Y} }

type Path []Point

func (path Path) TranslateBy(offset Point, add bool) {

var op func(p, q Point) Point

if add {

op = Point.Add

} else {

op = Point.Sub

}

for i := range path {

// Call either path[i].Add(offset) or path[i].Sub(offset).

path[i] = op(path[i], offset)

}

}

Encapsulation

Go has only one mechnism to control the visibility of names: capitalized identifiers are exported from the package in which they are defined, and uncaptitalized names are not. The same mechanism that limits access to memebers of a package also limits access to the fields of a struct or the methods of a type. As a consequnce, to encapsulation an object, we must make it struct.

type IntSet struct {

words []uint64

}

We could instead define IntSet as a slice type as follows:

type IntSet []uint64

Although this version of IntSet would be essentially equivalent, it would allow clients from other packages to read and modify the slice directly.

Another consequence of this name-based mechanism is that the unit of encapsulation is the package, not the type as in many other languages. The fields of a struct type are visible to all code within the same package. Whether the code appears in a function or a method makes no difference.

Function that merely access or modify interal values of a type, such as the method of the Logger type from log package, below, are called getters and setters. However, when naming a getter method, we usually omit the Get prefix. This preference for brevity extends to all methods, not just field accessors, and to other redundant prefixes as well, such as Fetch, Find, and Lookup.

package log

type Logger struct {

flags int

prefix string

// ...

}

func (l *Logger) Flags() int

func (l *Logger) SetFlags(flag int)

func (l *Logger) Prefix() string

func (l *Logger) SetPrefix(prefix string)

Encapsulation is not always desirable. By revealing its represention as an int64 number of nanoseconds, time.Duration lets us use all the usual arithmetic and comparsion operations with durations, and even to define constants of this type:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

const day = 24 * time.Hour

func main() {

fmt.Printf("%t\n", day) // %!t(time.Duration=86400000000000)

}

Interfaces

Interface types express generalizations or abstractions about the behaviors of other types. By generalizing, interfaces let us write functions that are more flexible and adaptable because they are not tied to the details of one particular implementation.

Many object-oriented languages have some notion of interface, but what makes Go’s interfaces so distinctive is they are satisfied implicitly. In other words, there’s no need to declare all the interfaces that a given concrete type satisfies; simply possessing the necessary methods is enough. This design lets you create new interfaces that are satisfied by existing concrete types without changing the existing types, which is particularly useful for types defined in packages that you don’t control.

Interface as Contracts

A concrete type specifies the exact representation of its values and exposes the intrinsic operations of that representation, such as arithmetric for numbers, or indexing, append, and range for slices. A concrete type may also provide additional behaviors through its methods. When you have a value of a concrete type, you knonw exactly what it is and what you can do with it.

An interface is an abstract type. It doesn’t expose the representation or iternal structure of its values, or the set of basic operations they support; it reveals only some of their methods. When you have a value of an interface type, you know nothing about what it is; you know only what it can do, or more precisely, what behaviors are provided by its methods.

Interface Types

An interface type specifies a set of methods that a concrete type must possess to be considered an instance of that interface.

The io.Writer type is one of the most widely used interfaces because it provides an abstraction of all the types to which bytes can be written, which includes files, memory buffers, network connections, HTTP clients, archivers, hashers, and so on. The io package defines many other useful interfaces. A Reader represents any type from which you can read bytes, and a Closer is any value that you can close, such as a file or a network connection.

package io

type Writer interface {

Write(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

type Reader interface {

Read(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

type Closer interface {

Close() error

}

Looking farther, we find declarations of new interface types as combinations of existing ones.

Here are two examples:

package io

// ReadWriter is the interface that groups the basic Read and Write methods.

type ReadWriter interface {

Reader

Writer

}

// ReadWriteCloser is the interface that groups the basic Read, Write and Close methods.

type ReadWriteCloser interface {

Reader

Writer

Closer

}

The syntax used above, which resembles struct embedding, lets us name another interface as a shorthand for writting out all of its methods. This is called embedding an interface.

Interface Satisfaction

A type *statisfies an interface if it possesses all the methods the interface requires. For example, an *os.File satisfies io.Reader, Writer, Closer, and ReadWriter. A *bytes.Buffer satisfies Reader, Writer, and ReadWriter, but does not satisfy Closer because it does not have a Close method.

The assignability rule for interfaces is very simple: an expression may be assigned to an interface only if its type satifies the interface. So:

var w io.Writer

w = os.Stdout // OK: *os.File has Write method

w = new(bytes.Buffer) // OK: *bytes.Buffer has Write method

w = time.Second // compile error: time.Duration lacks Write method

var rwc io.ReadWriteCloser

rwc = os.Stdout // OK: *os.File has Read, Write, Close methods

rwc = new(bytes.Buffer) // compile error: *bytes.Buffer lacks Close method

This rule applies even when the right-hand side is itself an interface:

w = rwc // OK: io.ReadWriteCloser has Write method

rwc = w // compile error: io.Writer lacks Close method

The type interface{}, which is called the empty interface type places no demands on the types that statisfy it, we can assign any value to the empty interface.

var any interface{}

any = true

any = 12.34

any = "hello"

any = map[string]int{"one": 1}

any = new(bytes.Buffer)

Since interface satisfcation depends only on the methods of the two type involved, there is no need to declare the relationship between a concrete type and the interface it satifies. That said, it is occasionally useful to document and assert the relationship when it is intended but not otherwise enforced by the program. The declaration below assets at compile time that a value of type *bytes.Buffer satifies io.Writer:

// *bytes.Buffer must satisfy io.Writer

var w io.Writer = new(bytes.Buffer)

We needn’t allocate a new variable since any value of type *bytes.Buffer will do, even nil, which we writes as (*bytes.Buffer)(nil) using an explicit conversion. And since we never intend to refer to w, we can replace it with the blank identifier. Together, these changes give us this more frugal variant:

// *bytes.Buffer must satisfy io.Writer

var _ io.Writer = (*bytes.Buffer)(nil)

Interface Values

Conceptually, a value of an interface type, or interface value, has two components, a concrete type and a value of that type. These are called the interface’s dynamic type and dynamic value.

For a statically typed language like Go, types are a compile-time concept, so a type is not a value. In our conceptual model, a set of values called type descriptors provide information about each type, such as its name and methods. In an interface value, the type component is represented by the appropriate type descriptor.

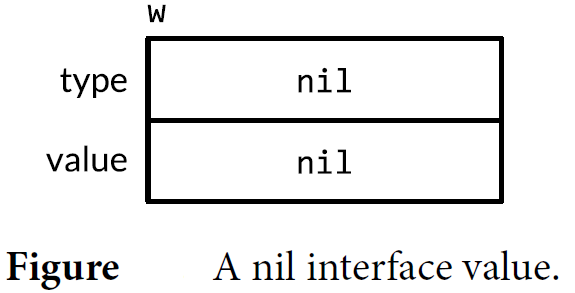

The zero value for an interface has both its type and value components set to nil.

var w io.Writer

An interface value is described as nil or non-nil based on its dynamic type, so this is a nil interface value.

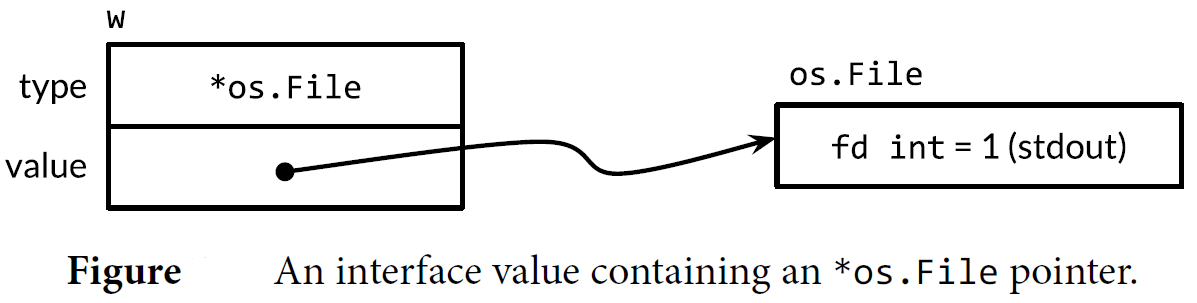

The below statement assigns a value of type *os.File to w:

var w io.Writer = os.Stdout

This assignment involves an implicit conversion from a concrete type to an interface type, and is equivalent to the explicit conversion io.Writer(os.Stdout). A conversion of this kind, whether explicit or implicit, captures the type and the value of its operand. The interface values’ dynamic type is set to the type descriptor for the pointer type *os.File, and its dynamic value holds a copy of os.Stdout, which is a pointer to the os.File variable representing the standard output of process.

Calling the Write method on an interface value containing an *os.File pointer causes the (*os.File).Write method to be called. The call prints “hello”.

w.Write([]byte("hello")) // "hello"

In general, we cannot know at compile time that what the dynamic type of an interface value will be, so a call through an interface must use dynamic dispatch. Instead of a direct call, the compiler must generate code to obtain the address of the method named Write from the type descriptor, then make an indirect call to the address. The receiver argument for the call is a copy of the interface’s dynamic value, os.Stdout. The effect is as if we had make this call directly:

os.Stdout.Write([]byte("hello")) // "hello"

Interface values may be compared using == and !=. Two interface values are equal if both are nil, or if their dynamic types are identical and their dynmaic values are equal according to the usual behavior of == for that type. However, if two interface values are compared and have the same dynamic type, but the that type is not comparable (a slice, for instance), then the comparision fails with a panic:

var x interface{} = []int{1, 2, 3}

fmt.Println(x == x) // panic: comparing uncomparable type []int

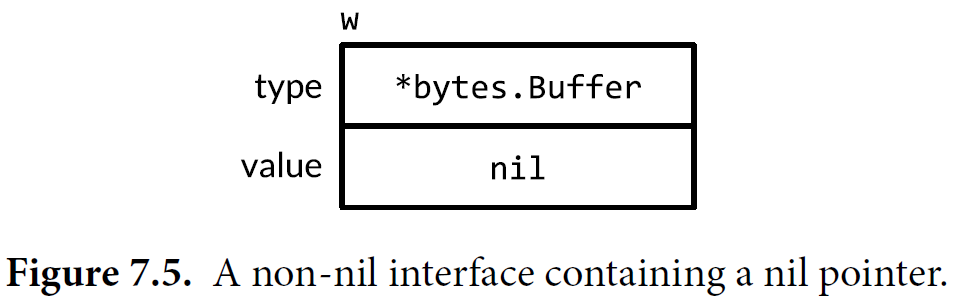

Caveat: An Interface Containing a Nil Pointer Is Non-Nil

A nil interface value, which contains no value at all, is not the same as an interface value containing a pointer that happens to be nil.

package main

import (

"bytes"

"io"

)

func main() {

var buf *bytes.Buffer

var out io.Writer

out = buf // NOTE: subtly incorrect!

if out != nil {

out.Write([]byte("done!\n")) // panic: runtime error: invalid memory address or nil pointer dereference

}

}

Type Assertions

A type assertion is an operation applied to an interface value. Syntactically, it looks like x.(T), where x is an expression of an interface type and T is a type, called the “asserted” type. A type assertion checks that the dynamic type of its operand matches the asserted type.

A type assertion to a concrete type extracts the concrete value from its operand. If the check fails, then the operation panics.

var w io.Writer

w = os.Stdout

f := w.(*os.File) // success: f == os.Stdout

c := w.(*bytes.Buffer) // panic: interface holds *os.File, not *bytes.Buffer

A type assertion to an interface type changes the type of the expression, making a different (and usually larger) set of methods accessible, but it preserves the dynamic type and value components inside the interface.

var w io.Writer

w = os.Stdout

rw := w.(io.ReadWriter) // success: *os.File has both Read and Write

w = new(ByteCounter)

rw = w.(io.ReadWriter) // panic: *ByteCounter has no Read method

No matter what type was asserted, if the operand is a nil interface value, the value assertion fails.

If the type assertion appears is an assignment in which two results are expected, such as the following declarations, the operation does not panic on failure but instead returns an additional second result, a boolean indicating success.

var w io.Writer = os.Stdout

f, ok := w.(*os.File) // success: ok, f == os.Stdout

b, ok := w.(*bytes.Buffer) // failure: !ok, b == nil

When the operand of a type assertion is a variable, rather than invent another name for the new local variable, you’ll sometimes see the original name reused, shadowing the original, like this:

var w io.Writer = os.Stdout

if w, ok := w.(*os.File); ok {

w.Write([]byte("Hello world"))

// ...use w...

}

Type Switches

Interfaces are used in two distinct styles. In the first style, exemplified by io.Reader, io.Writer, fmt.Stringer, sort.Interface, http.Handler, and error, an interface’s methods express the similarities of the concrete types that satisfy the interface but hide the representation detail and intrinsic operations of those concrete types. The emphasis is on the methods, not on the concrete types.

The second style exploits the ablility of an interface value to hold values of a variety of concrete types and considers the interface to be the union of those types. Type assertions are used to discriminate among these types dynamically and treat each case differently. In this style, the emphasis is on the concrete types that satisfy the interface, not on the interface’s methods (if indeed it has any), and there is no hiding of information.

Go’s API for quering an SQL database, like those of other languages, lets us cleanly separate the fixed part of a query from the variable parts. An example client might look like this:

import "database/sql"

func listTracks(db sql.DB, artist string, minYear, maxYear int) {

result, err := db.Exec(

"SELECT * FROM tracks WHERE artist = ? AND ? <= year AND year <= ?",

artist, minYear, maxYear)

// ...

}

The Exec method replace each ‘?’ in the query string with an SQL literal denoting the coresponding argument value, which may be a boolean, a number, a string, or nil. Within Exec, we might find a function like the one below, which converts each argument value to its literal SQL notation.

func sqlQuote(x interface{}) string {

if x == nil {

return "NULL"

} else if _, ok := x.(int); ok {

return fmt.Sprintf("%d", x)

} else if _, ok := x.(uint); ok {

return fmt.Sprintf("%d", x)

} else if b, ok := x.(bool); ok {

if b {

return "TRUE"

}

return "FALSE"

} else if s, ok := x.(string); ok {

return sqlQuoteString(s) // (not shown)

} else {

panic(fmt.Sprintf("unexpected type %T: %v", x, x))

}

}

A switch statement simplifies an if-else chain that performs a series of value equality tests. An analogous type switch statement simplifies an if-else chain of type assertions.

In its simplest form, a type switch looks like an oridinary switch statement in which the operand is x.(type)—that’s literally the keyword type—and each case has one or more types. A type switch enables a multi-way branch based on the interface value’s dynamic type. The nil case matchs if x == nil, and the default case matches if no other case does. No fallthrough is allowed. A type switch for sqlQuote would have these cases:

switch x.(type) {

case nil: // ...

case int, uint: // ...

case bool: // ...

case string: // ...

default: // ...

}

Typically, the type switch statement has an extended form that binds the extracted value to a new variable within each case:

switch x := x.(type) {

// ...

}

Like a switch statement, a type switch implicitly creates a lexical block, so the declration of the new variable called x does not conflict with a variable x in an outer block. Each case also implicitly creates a separate lexical block.

Rewriting sqlQuote to use the extended form of type switch makes it significantly clearer:

func sqlQuote(x interface{}) string {

switch x := x.(type) {

case nil:

return "NULL"

case int, uint:

return fmt.Sprintf("%d", x) // x has type interface{} here.

case bool:

if x {

return "TRUE"

}

return "FALSE"

case string:

return sqlQuoteString(x) // (not shown)

default:

panic(fmt.Sprintf("unexpected type %T: %v", x, x))

}

}

References

- Alan A. A. Donovan, Brian W. Kernighan. The Go Programming Language, 2015.11.

- Interface types, The Go Programming Language Specification.

- Interface names, Effective Go - The Go Programming Language