- 1. Docker Storage Drivers and Volumes

- 2. Kubernetes Volumes

- 3. CSI Storage Drivers on Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS)

- Referenes

1. Docker Storage Drivers and Volumes

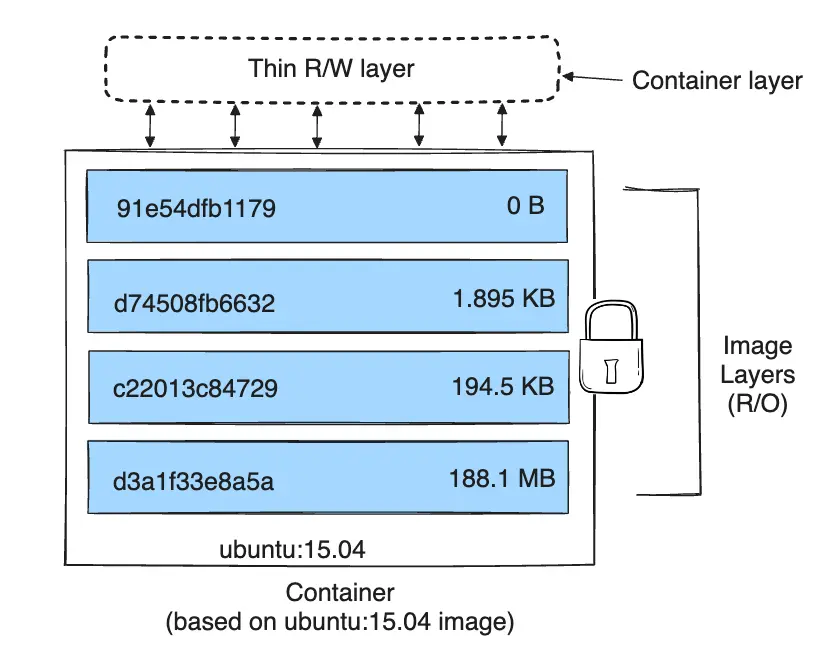

Docker uses storage drivers to store image layers, and to store data in the writable layer of a container. [1]

Storage drivers are optimized for space efficiency, but (depending on the storage driver) write speeds are lower than native file system performance, especially for storage drivers that use a copy-on-write filesystem.

Use Docker volumes for write-intensive data, data that must persist beyond the container’s lifespan, and data that must be shared between containers.

1.1. Storage Drivers

A Docker image is built up from a series of layers. Each layer represents an instruction in the image’s Dockerfile. Each layer except the very last one is read-only. Consider the following Dockerfile:

# syntax=docker/dockerfile:1

FROM ubuntu:22.04

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.authors="org@example.com"

COPY . /app

RUN make /app

RUN rm -r $HOME/.cache

CMD python /app/app.pyThis Dockerfile contains four commands. Commands that modify the filesystem create a layer.

-

The

FROMstatement starts out by creating a layer from theubuntu:22.04image. -

The

LABELcommand only modifies the image’s metadata, and doesn’t produce a new layer. -

The

COPYcommand adds some files from your Docker client’s current directory. -

The first

RUNcommand builds your application using the make command, and writes the result to a new layer.The second

RUNcommand removes a cache directory, and writes the result to a new layer. -

Finally, the

CMDinstruction specifies what command to run within the container, which only modifies the image’s metadata, which doesn’t produce an image layer.

When a new container is created, a new writable layer is added on top of the underlying layers, which is often called the container layer.

A storage driver handles the details about the way these layers interact with each other.

To see what storage driver Docker is currently using, use docker info and look for the Storage Driver line:

$ docker info 2> /dev/null | grep 'Storage Driver' -A 5

Storage Driver: overlay2

Backing Filesystem: extfs

Supports d_type: true

Using metacopy: false

Native Overlay Diff: true

userxattr: false

$ df -T /var/lib/docker

Filesystem Type 1K-blocks Used Available Use% Mounted on

/dev/sda1 ext4 102624184 57865288 39499736 60% /|

containerd, the industry-standard container runtime, uses snapshotters instead of the classic storage drivers for storing image and container data. While the

|

1.2. Volumes

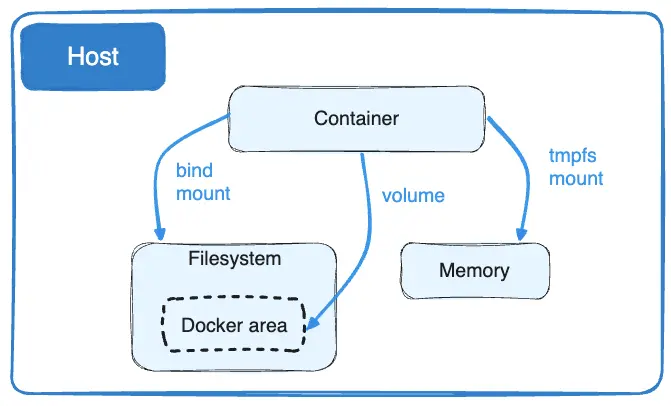

Docker has two options for containers to store files on the host machine, so that the files are persisted even after the container stops: volumes, and bind mounts. [3]

-

Volumes are stored in a part of the host filesystem which is managed by Docker (

/var/lib/docker/volumes/on Linux). Non-Docker processes should not modify this part of the filesystem. Volumes are the best way to persist data in Docker. -

Bind mounts may be stored anywhere on the host system. They may even be important system files or directories. Non-Docker processes on the Docker host or a Docker container can modify them at any time.

-

tmpfs mounts are stored in the host system’s memory only, and are never written to the host system’s filesystem.

2. Kubernetes Volumes

Kubernetes volumes provide a way for containers in a pods to access and share data via the filesystem, facilitating the data sharing can be between different local processes within a container, or between different containers, or between Pods. [4]

Kubernetes supports many types of volumes. Ephemeral volume types have a lifetime of a pod, but persistent volumes exist beyond the lifetime of a pod. [4]

-

To use a volume, specify the volumes to provide for the Pod in

.spec.volumesand declare where to mount those volumes into containers in.spec.containers[*].volumeMounts. -

The

volumeMounts[*].subPathproperty specifies a sub-path inside the referenced volume instead of its root.Kubernetes will only mount the specified path or file from the volume into the container’s filesystem at the given

mountPath.apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: test-pod spec: containers: - name: test-container image: busybox:stable command: ['tail', '-f', '/dev/null'] volumeMounts: - name: test-data mountPath: /var/lib/test-data/foo subPath: foo - name: test-data-file mountPath: /var/lib/test-data/hello.txt subPath: hello.txt volumes: - name: test-data hostPath: path: /tmp/test-data - name: test-data-file hostPath: path: /tmp/test-data/foo$ tree /tmp/test-data/ /tmp/test-data/ ├── bar │ └── world.txt └── foo └── hello.txt $ kubectl exec test-pod -- ls -l /var/lib/test-data/ total 8 drwxr-xr-x 2 1000 1000 4096 Feb 26 07:22 foo -rw-r--r-- 1 1000 1000 6 Feb 26 07:22 hello.txt $ kubectl exec test-pod -- ls -l /var/lib/test-data/foo total 4 -rw-r--r-- 1 1000 1000 6 Feb 26 07:22 hello.txt -

The

subPathExpr, mutually exclusive withsubPath, can be used to dynamically createsubPathdirectory names using downward API environment variables. -

A mount can be made read-only by setting the

.spec.containers[].volumeMounts[].readOnlyfield totrue. -

Recursive read-only mounts can be enabled by setting the

.spec.containers[].volumeMounts[].recursiveReadOnlyfield for a pod. -

A process in a container sees a filesystem view composed from the initial contents of the container image, plus volumes (if defined) mounted inside the container.

-

Mount propagation of a volume is controlled by the

mountPropagationfield incontainers[*].volumeMountsfor sharing volumes mounted by a container to other containers in the same pod, or even to other pods on the same node.-

None- The volume mount will not receive any subsequent mounts that are mounted to this volume or any of its subdirectories by the host, and no mounts created by the container will be visible on the host. -

HostToContainer- The volume mount will receive all subsequent mounts that are mounted to it or any of its subdirectories. -

Bidirectional- The volume mount behaves the same theHostToContainermount, and all volume mounts created by the container will be propagated back to the host and to all containers of all pods that use the same volume.

-

-

The storage media (such as Disk or SSD) of an

emptyDirvolume is determined by the medium of the filesystem holding the kubelet root dir (typically/var/lib/kubelet). -

There is no limit on how much space an

emptyDirorhostPathvolume can consume, and no isolation between containers or pods.

Kubernetes supports several types of volumes.

-

configMap

A

configMapvolume is used to inject configuration data from aConfigMapinto a Pod, which is backed by a directory mounted on the pod’s filesystem, making the data accessible to containerized applications. -

secret

A

secretvolume is used to pass sensitive information, such as passwords, from aSecretinto a Pod, which is backed by tmpfs (a RAM-backed filesystem) so they are never written to non-volatile storage. -

downwardAPI

A

downwardAPIvolume makes downward API data available to applications, exposing data as read-only files in plain text format. -

emptyDir

An

emptyDirvolume provides temporary scratch space, created as empty directory when a pod is scheduled to a node, allowing all containers within the pod to share the same files.-

When a Pod is removed from a node for any reason, the data in the

emptyDiris deleted permanently. -

The data in an

emptyDirvolume is safe across container crashes, as a container crashing does not remove a Pod from a node. -

By default

emptyDirvolumes are stored on whatever medium that backs the node such as disk, SSD, or network storage, determined by the medium of the filesystem holding the kubelet root dir (typically/var/lib/kubelet). -

If the

emptyDir.mediumfield is set toMemory, Kubernetes mounts a tmpfs (RAM-backed filesystem) instead. -

The kubelet tracks tmpfs

emptyDirvolumes as container memory use, which is constrained by the memory limit for the Pod or container, rather than as local ephemeral storage.

-

-

hostPath

A

hostPathvolume mounts a file or directory from the host node’s filesystem into a Pod. -

local

A

localvolume represents a mounted local storage device such as a disk, partition or directory.Local volumes can only be used as a statically pre-created

PersistentVolume.It is recommended to create a

StorageClasswithvolumeBindingMode: WaitForFirstConsumer.apiVersion: storage.k8s.io/v1 kind: StorageClass metadata: name: local-storage provisioner: kubernetes.io/no-provisioner volumeBindingMode: WaitForFirstConsumer -

nfs

An

nfsvolume allows an existing NFS (Network File System) share to be mounted into a Pod by multiple writers simultaneously. -

persistentVolumeClaim

A

persistentVolumeClaimvolume is a way for users to "claim" durable storage (such as an iSCSI volume) without knowing the details of the particular cloud environment to mount a PersistentVolume into a Pod. -

projected

A

projectedvolume maps several existing volume sources into the same directory.

2.1. ConfigMaps

A ConfigMap is an API object used to store non-confidential data in key-value pairs, that can be consumed by a Pod as environment variables, command-line arguments, or as configuration files in a volume.

-

A

ConfigMaphasdataandbinaryDatafields that accept key-value pairs as their values.-

Both the

datafield and thebinaryDataare optional. -

The

datafield is designed to contain UTF-8 strings while thebinaryDatafield is designed to contain binary data as base64-encoded strings.

-

-

When a

ConfigMapcurrently consumed in a volume is updated, projected keys are eventually updated as well.-

The kubelet checks whether the mounted

ConfigMapis fresh on every periodic sync. However, the kubelet uses its local cache for getting the current value of theConfigMap. -

A

ConfigMapcan be either propagated by watch (default), ttl-based, or by redirecting all requests directly to the API server. -

A

ConfigMapconsumed as environment variable is not updated automatically and require a pod restart. -

A container using a

ConfigMapas asubPathvolume mount will not receiveConfigMapupdates.

-

-

A

ConfigMapcan be created either usingkubectl create configmapor aConfigMapgenerator inkustomization.yaml.$ kubectl create cm game-config --from-file configure-pod-container/configmap/ configmap/game-config created $ kubectl get cm game-config -oyaml apiVersion: v1 data: game.properties: |- enemies=aliens lives=3 enemies.cheat=true enemies.cheat.level=noGoodRotten secret.code.passphrase=UUDDLRLRBABAS secret.code.allowed=true secret.code.lives=30 ui.properties: | color.good=purple color.bad=yellow allow.textmode=true how.nice.to.look=fairlyNice kind: ConfigMap metadata: creationTimestamp: "2025-02-26T06:27:24Z" name: game-config namespace: default resourceVersion: "373961" uid: fe6e6cf4-2d05-4152-af8f-b2563514d851$ kubectl create cm game-config-2 \ --from-env-file configure-pod-container/configmap/game.properties \ --from-env-file configure-pod-container/configmap/ui.properties configmap/game-config-2 created $ kubectl get cm game-config-2 -oyaml apiVersion: v1 data: allow.textmode: "true" color.bad: yellow color.good: purple enemies: aliens enemies.cheat: "true" enemies.cheat.level: noGoodRotten how.nice.to.look: fairlyNice lives: "3" secret.code.allowed: "true" secret.code.lives: "30" secret.code.passphrase: UUDDLRLRBABAS kind: ConfigMap metadata: creationTimestamp: "2025-02-26T06:29:05Z" name: game-config-2 namespace: default resourceVersion: "374137" uid: a6094626-907f-412a-a2d1-5b3fdda225aa$ kubectl create configmap special-config \ --from-literal SPECIAL_LEVEL=very \ --from-literal SPECIAL_TYPE=charm configmap/special-config created $ kubectl get cm special-config -oyaml apiVersion: v1 data: SPECIAL_LEVEL: very SPECIAL_TYPE: charm kind: ConfigMap metadata: creationTimestamp: "2025-02-26T06:36:29Z" name: special-config namespace: default resourceVersion: "374899" uid: 4d194d31-5fe3-4255-8ee9-e951943d92db

2.2. Secrets

A Secret is an object, similar to a ConfigMap but is specifically intended to hold confidential data, that contains a small amount of sensitive data such as a password, a token, or a key.

-

Kubernetes offers built-in types for common scenarios, varying in validation and imposed constraints.

kubectl create secret generic empty-secret kubectl get secret empty-secretkubectl create secret docker-registry secret-tiger-docker \ --docker-email=tiger@acme.example \ --docker-username=tiger \ --docker-password=pass1234 \ --docker-server=my-registry.example:5000kubectl create secret tls my-tls-secret \ --cert=path/to/cert/file \ --key=path/to/key/fileapiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: foo namespace: awesomeapps spec: containers: - name: foo image: janedoe/awesomeapp:v1 imagePullSecrets: - name: myregistrykeyapiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1 kind: Ingress metadata: name: dev.test spec: rules: - host: dev.test http: paths: - backend: service: name: echoserver port: number: 80 path: / pathType: ImplementationSpecific tls: - hosts: - '*.dev.test' secretName: dev.test

2.3. Container Storage Interface (CSI)

Container Storage Interface (CSI) defines a standard interface for container orchestration systems (like Kubernetes) to expose arbitrary storage systems to their container workloads.

Once a CSI compatible volume driver is deployed on a Kubernetes cluster, users may use the csi volume type to attach or mount the volumes exposed by the CSI driver.

A csi volume can be used in a Pod in three different ways:

-

through a reference to a PersistentVolumeClaim

-

with a generic ephemeral volume

-

with a CSI ephemeral volume if the driver supports that

The following fields are available to storage administrators to configure a CSI persistent volume:

-

driver: A string value that specifies the name of the volume driver to use. -

volumeHandle: A string value that uniquely identifies the volume. -

readOnly: An optional boolean value indicating whether the volume is to be "ControllerPublished" (attached) as read only. Default is false. -

fsType: If the PV’sVolumeModeisFilesystemthen this field may be used to specify the filesystem that should be used to mount the volume.If the volume has not been formatted and formatting is supported, this value will be used to format the volume.

-

volumeAttributes: A map of string to string that specifies static properties of a volume. -

controllerPublishSecretRef: A reference to the secret object containing sensitive information to pass to the CSI driver to complete the CSIControllerPublishVolumeandControllerUnpublishVolumecalls. -

nodeExpandSecretRef: A reference to the secret containing sensitive information to pass to the CSI driver to complete the CSINodeExpandVolumecall. -

nodePublishSecretRef: A reference to the secret object containing sensitive information to pass to the CSI driver to complete the CSINodePublishVolumecall. -

nodeStageSecretRef: A reference to the secret object containing sensitive information to pass to the CSI driver to complete the CSINodeStageVolumecall.

2.4. Persistent Volumes

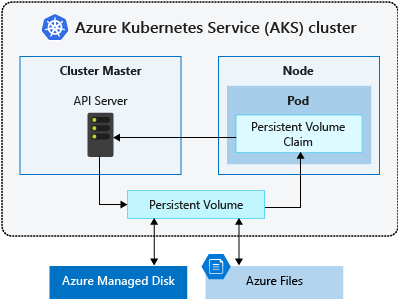

Managing storage is a distinct problem from managing compute instances. The PersistentVolume subsystem provides an API for users and administrators that abstracts details of how storage is provided from how it is consumed.

A PersistentVolume (PV) is a piece of storage in the cluster that has been provisioned by an administrator or dynamically provisioned using Storage Classes.

-

It is a resource in the cluster just like a node is a cluster resource, that captures the details of the implementation of the storage, be that NFS, iSCSI, or a cloud-provider-specific storage system.

-

PVs are volume plugins like Volumes, but have a lifecycle independent of any individual Pod that uses the PV.

A PersistentVolumeClaim (PVC) is a request for storage by a user. It is similar to a Pod.

-

Pods consume node resources and PVCs consume PV resources. Pods can request specific levels of resources (CPU and Memory).

-

Claims can request specific size and access modes (e.g., ReadWriteOnce, ReadOnlyMany, ReadWriteMany, or ReadWriteOncePod).

-

While PersistentVolumeClaims allow a user to consume abstract storage resources, it is common that users need PersistentVolumes with varying properties, such as performance, for different problems.

A StorageClass provides a way for administrators to describe the classes of storage they offer. Different classes might map to quality-of-service levels, or to backup policies, or to arbitrary policies determined by the cluster administrators. [5]

-

Each StorageClass contains the fields

provisioner,parameters, andreclaimPolicy, which are used when a PersistentVolume belonging to the class needs to be dynamically provisioned to satisfy a PersistentVolumeClaim (PVC). -

The name of a StorageClass object is significant, and is how users can request a particular class. Administrators set the name and other parameters of a class when first creating StorageClass objects.

apiVersion: storage.k8s.io/v1 kind: StorageClass metadata: name: local-storage provisioner: kubernetes.io/no-provisioner volumeBindingMode: WaitForFirstConsumer

2.4.1. Lifecycle of a volume and claim

PVs are resources in the cluster. PVCs are requests for those resources and also act as claim checks to the resource. The interaction between PVs and PVCs follows this lifecycle: [6]

2.4.1.1. Provisioning

There are two ways PVs may be provisioned: statically or dynamically.

-

Static

A cluster administrator creates a number of PVs. They carry the details of the real storage, which is available for use by cluster users. They exist in the Kubernetes API and are available for consumption.

-

Dynamic

When none of the static PVs the administrator created match a user’s PersistentVolumeClaim, the cluster may try to dynamically provision a volume specially for the PVC based on StorageClasses.

2.4.1.2. Binding

A control loop in the control plane watches for new PVCs, finds a matching PV (if possible), and binds them together.

-

If a PV was dynamically provisioned for a new PVC, the loop will always bind that PV to the PVC.

-

Otherwise, the user will always get at least what they asked for, but the volume may be in excess of what was requested.

The volumeBindingMode field of a StorageClass controls when volume binding and dynamic provisioning should occur, and when unset, Immediate mode is used by default. [5]

-

The

Immediatemode indicates that volume binding and dynamic provisioning occurs once the PersistentVolumeClaim is created.For storage backends that are topology-constrained and not globally accessible from all Nodes in the cluster, PersistentVolumes will be bound or provisioned without knowledge of the Pod’s scheduling requirements. This may result in unschedulable Pods.

-

A cluster administrator can address this issue by specifying the

WaitForFirstConsumermode which will delay the binding and provisioning of a PersistentVolume until a Pod using the PersistentVolumeClaim is created.PersistentVolumes will be selected or provisioned conforming to the topology that is specified by the Pod’s scheduling constraints.

2.4.1.3. Using

Pods use claims as volumes.

-

The cluster inspects the claim to find the bound volume and mounts that volume for a Pod.

-

For volumes that support multiple access modes, the user specifies which mode is desired when using their claim as a volume in a Pod.

2.4.1.4. Storage Object in Use Protection

If a user deletes a PVC in active use by a Pod, the PVC is not removed immediately. PVC removal is postponed until the PVC is no longer actively used by any Pods. Also, if an admin deletes a PV that is bound to a PVC, the PV is not removed immediately. PV removal is postponed until the PV is no longer bound to a PVC.

2.4.1.5. Reclaiming

The reclaim policy for a PersistentVolume tells the cluster what to do with it after it has been released of its claim, which can either be Retained or Deleted.

2.4.1.6. PersistentVolume deletion protection finalizer

FEATURE STATE: Kubernetes v1.23 [alpha]

Finalizers can be added on a PersistentVolume to ensure that PersistentVolumes having Delete reclaim policy are deleted only after the backing storage are deleted.

The newly introduced finalizers kubernetes.io/pv-controller and external-provisioner.volume.kubernetes.io/finalizer are only added to dynamically provisioned volumes.

-

The finalizer

kubernetes.io/pv-controlleris added to in-tree plugin volumes. -

The finalizer

external-provisioner.volume.kubernetes.io/finalizeris added for CSI volumes.

2.4.1.7. Reserving a PersistentVolume

If you want a PVC to bind to a specific PV, you need to pre-bind them.

-

By specifying a PersistentVolume in a PersistentVolumeClaim, you declare a binding between that specific PV and PVC.

-

If the PersistentVolume exists and has not reserved PersistentVolumeClaims through its

claimReffield, then the PersistentVolume and PersistentVolumeClaim will be bound. -

The binding happens regardless of some volume matching criteria, including node affinity.

The control plane still checks that storage class, access modes, and requested storage size are valid.

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

metadata:

name: foo-pvc

namespace: foo

spec:

# Empty string must be explicitly set otherwise default StorageClass will be set.

storageClassName: ""

volumeName: foo-pv

...

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolume

metadata:

name: foo-pv

spec:

storageClassName: ""

claimRef:

name: foo-pvc

namespace: foo

...2.4.1.8. Expanding Persistent Volumes Claims

FEATURE STATE: Kubernetes v1.24 [stable]

To request a larger volume for a PVC, edit the PVC object and specify a larger size. This triggers expansion of the volume that backs the underlying PersistentVolume. A new PersistentVolume is never created to satisfy the claim. Instead, an existing volume is resized.

You can only expand a PVC if its storage class’s allowVolumeExpansion field is set to true.

2.4.2. Claims As Volumes

Pods access storage by using the claim as a volume.

-

Claims must exist in the same namespace as the Pod using the claim.

-

The cluster finds the claim in the Pod’s namespace and uses it to get the PersistentVolume backing the claim.

-

The volume is then mounted to the host and into the Pod.

2.4.3. Raw Block Volume Support

FEATURE STATE: Kubernetes v1.18 [stable]

The following volume plugins support raw block volumes, including dynamic provisioning where applicable:

-

CSI

-

FC (Fibre Channel)

-

iSCSI

-

Local volume

-

OpenStack Cinder

-

RBD (deprecated)

-

RBD (Ceph Block Device; deprecated)

-

VsphereVolume

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolume

metadata:

name: block-pv

spec:

accessModes:

- ReadWriteOnce

capacity:

storage: 5Gi

local:

path: /dev/sdb

nodeAffinity:

required:

nodeSelectorTerms:

- matchExpressions:

- key: node.local.io/block-storage

operator: In

values:

- local

persistentVolumeReclaimPolicy: Retain

storageClassName: local-storage

volumeMode: Block

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

metadata:

name: block-pvc

spec:

accessModes:

- ReadWriteOnce

resources:

limits:

storage: 5Gi

requests:

storage: 5Gi

storageClassName: local-storage

volumeMode: Block

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: pod-with-block-volume

spec:

containers:

- name: busybox

image: busybox:stable

command: ["/bin/sh", "-c"]

args: [ "tail -f /dev/null" ]

volumeDevices:

- name: data

devicePath: /dev/xvda

volumes:

- name: data

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: block-pvc$ lsblk

NAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINTS

loop0 7:0 0 10G 0 loop

sda 8:0 0 100G 0 disk

└─sda1 8:1 0 100G 0 part /

sdb 8:16 0 10G 0 disk

$ kubectl get storageclasses.storage.k8s.io local-storage

NAME PROVISIONER RECLAIMPOLICY VOLUMEBINDINGMODE ALLOWVOLUMEEXPANSION AGE

local-storage kubernetes.io/no-provisioner Delete WaitForFirstConsumer false 3d11h3. CSI Storage Drivers on Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS)

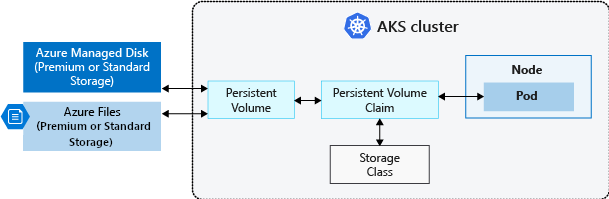

The Container Storage Interface (CSI) is a standard for exposing arbitrary block and file storage systems to containerized workloads on Kubernetes.

By adopting and using CSI, Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS) can write, deploy, and iterate plug-ins to expose new or improve existing storage systems in Kubernetes without having to touch the core Kubernetes code and wait for its release cycles. [6]

A PersistentVolumeClaim requests storage of a particular StorageClass, access mode, and size. The Kubernetes API server can dynamically provision the underlying Azure storage resource if no existing resource can fulfill the claim based on the defined StorageClass.

The CSI storage driver support on AKS allows you to natively use:

-

Azure Disks can be used to create a Kubernetes DataDisk resource.

Disks can use Azure Premium Storage, backed by high-performance SSDs, or Azure Standard Storage, backed by regular HDDs or Standard SSDs. For most production and development workloads, use Premium Storage.

Azure Disks are mounted as ReadWriteOnce and are only available to one node in AKS. For storage volumes that can be accessed by multiple nodes simultaneously, use Azure Files.

kind: StorageClass apiVersion: storage.k8s.io/v1 metadata: name: azuredisk-csi-waitforfirstconsumer provisioner: disk.csi.azure.com parameters: skuname: StandardSSD_LRS allowVolumeExpansion: true reclaimPolicy: Delete volumeBindingMode: WaitForFirstConsumer -

Azure Files can be used to mount an SMB 3.0/3.1 share backed by an Azure storage account to pods.

With Azure Files, you can share data across multiple nodes and pods.

Azure Files can use Azure Standard storage backed by regular HDDs or Azure Premium storage backed by high-performance SSDs.

-

Azure Blob storage can be used to mount Blob storage (or object storage) as a file system into a container or pod.

Using Blob storage enables your cluster to support applications that work with large unstructured datasets like log file data, images or documents, HPC, and others.

Additionally, if you ingest data into Azure Data Lake storage, you can directly mount and use it in AKS without configuring another interim filesystem.