JavaScript is a cross-platform, prototype-based, object-oriented scripting language. The core language of JavaScript is standardized by the ECMA TC39 committee as a language named ECMAScript.

Among other things, ECMAScript defines:

-

Language syntax (parsing rules, keywords, control flow, object literal initialization, …)

-

Error handling mechanisms (

throw,try…catch, ability to create user-definedErrortypes) -

Types (

boolean,number,string,function,object, …) -

A prototype-based inheritance mechanism

-

Built-in objects and functions, including

JSON,Math,Arraymethods,parseInt,decodeURI, etc. -

Strict mode

-

A module system

-

Basic memory model

| The ECMAScript specification does not describe the Document Object Model (DOM), which is standardized by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and/or WHATWG (Web Hypertext Application Technology Working Group). |

| ECMAScript is the term for the language standard, but ECMAScript and JavaScript can be used interchangeably. |

| TypeScript stands in an unusual relationship to JavaScript, that offers all of JavaScript’s features, and an additional layer on top of these: TypeScript’s type system. |

| JavaScript is a developing language, new features get added regularly. To see their support among browser-based and other engines, see: https://caniuse.com – per-feature tables of support, e.g. to see which engines support modern cryptography functions: https://caniuse.com/#feat=cryptography. |

- 1. Basics

- 2. Control flow and error handling

- 3. Loops and iteration

- 4. Functions

- 5. Expressions and operators

- 6. Regular expressions

- 7. Indexed and keyed Collections

- 8. Date

- 9. JavaScript Object Notation (JSON)

- 10. Prototypes, objects and classes

- 11. Promises and asynchronous programming

- 12. Iterators and generators

- 13. Events

- 14. Modules

- 15. npm & npx

- Appendix A: Volta

- Appendix B: Vite

- Appendix C: React.js

- 16. References

1. Basics

JavaScript is case-sensitive and uses the Unicode character set.

const Hello世界 = 'Hello World!';

console.log(Hello世界); // logs "Hello World!"

console.log(hello世界); // Uncaught ReferenceError: hello世界 is not definedA semicolon (;) is not necessary after a statement if it is written on its own line. But if more than one statement on a line is desired, then they MUST be separated by semicolons.

const Hello世界 = 'Hello World!'; console.log(Hello世界) // logs "Hello World!"1.1. Comments

The syntax of comments is the same as in C++ and in many other languages:

// a one line comment

/* this is a longer,

* multi-line comment

*/1.2. Variables

JavaScript has three kinds of variable declarations.

-

varDeclares both local and global variables, depending on the execution context, optionally initializing it to a value.

-

letDeclares a block-scoped, local variable, optionally initializing it to a value.

-

constDeclares a block-scoped, read-only named constant.

| Variables should always be declared before they are used. JavaScript used to allow assigning to undeclared variables, which creates an undeclared global variable. |

If a variable is declared without an initializer, it is assigned the value undefined.

let x;

console.log(x); // logs "undefined"1.3. Scopes

A variable may belong to one of the following scopes:

-

Global scope: The default scope for all code running in script mode.

-

Module scope: The scope for code running in module mode.

-

Function scope: The scope created with a function.

-

Block scope: The scope created (

let,const) with a pair of curly braces (a block).

A variable declared outside a function is a global variable and is available to any other code in the current document, while a variable declared within a function is a local variable and is available only within that function.

-

Global variables are in fact properties of the global object.

-

In web pages, the global object is window, so global variables can be read and set using the

window.variablesyntax. -

In all environments, the globalThis variable (which itself is a global variable) may be used to read and set global variables, providing a consistent interface among various JavaScript runtimes.

-

Blocks only scope

letandconstdeclarations, but notvardeclarations.{ var x = 1; } console.log(x); // 1{ const x = 1; } console.log(x); // ReferenceError: x is not defined{ const x = 1; } { const x = 2; // Another block-scoped `x` } const x = 3; // A third `x` in the outer scope -

Variables declared with legacy

varare hoisted, meaning they can be referred to anywhere within their function-scope or global-scope, even if their declaration isn’t reached yet.// Example 1: Hoisting in global scope console.log(globalMessage); // Output: undefined (variable is hoisted, but not yet assigned) var globalMessage = 'Hello from global scope!'; console.log(globalMessage); // Output: Hello from global scope! function showVarHoisting() { // Example 2: Hoisting in function scope console.log(functionMessage); // Output: undefined (variable is hoisted within the function) var functionMessage = 'Hello from function scope!'; console.log(functionMessage); // Output: Hello from function scope! // Example 3: 'var' is NOT block-scoped if (true) { var blockMessage = 'I am inside an if block.'; console.log(blockMessage); // Output: I am inside an if block. } // 'blockMessage' is still accessible outside the 'if' block // because 'var' is function-scoped (to showVarHoisting), not block-scoped. console.log(blockMessage); // Output: I am inside an if block. } showVarHoisting(); // console.log(functionMessage); // This would cause a ReferenceError, as functionMessage is scoped to showVarHoisting. // console.log(blockMessage); // This would also cause a ReferenceError, as blockMessage is scoped to showVarHoisting.

1.4. Types

-

The ECMAScript standard defines seven primitives (

boolean,number,bigint,string,symbol,null, andundefined) and theobjecttype.-

Boolean.

trueandfalse. -

null. A special keyword denoting a null value. (Because JavaScript is case-sensitive,

nullis not the same asNull,NULL, or any other variant.) -

undefined. A top-level property whose value is not defined.

-

Number. An integer or floating point number. For example:

42or3.14159.In JavaScript, Number is a numeric data type in the double-precision 64-bit floating point format (IEEE 754). -

BigInt. An integer with arbitrary precision. For example:

9007199254740992n. -

String. A sequence of characters that represent a text value. For example:

"Howdy",'Howdy',`Howdy`. -

Symbol. A data type whose instances are unique and immutable.

-

Object. A collection of key-value pairs, where the values can be data or functions (i.e. methods). For example:

{ name: 'John', sayHello() { console.log('Hello!'); } }.

-

-

JavaScript is a dynamically typed language, which means that data types are automatically converted as-needed during script execution.

let answer = 42; typeof answer // 'number' answer = "Thanks for all the fish!"; typeof answer // 'string' x = "The answer is " + 42; // "The answer is 42" y = 42 + " is the answer"; // "42 is the answer" z = "37" + 7; // "377" "37" - 7; // 30 "37" * 7; // 259 // An alternative method of retrieving a number from a string is with the `+` (unary plus) operator: // Note: the parentheses are added for clarity, not required. "1.1" + "1.1"; // '1.11.1' (+"1.1") + (+"1.1"); // 2.2// String conversion String(true) // 'true' String(false) // 'false' String(0) // '0' String(NaN) // 'NaN' String(null) // 'null' String(undefined) // 'undefined' // Numeric conversion Number(true) // 1 Number(false) // 0 Number(null) // 0 Number(undefined) // NaN Number('') // 0 Number('\n') // 0 Number('123\n') // 123 // Boolean conversion Boolean('') // false Boolean(null) // false Boolean(undefined) // false Boolean(NaN) // false Boolean(0) // false Boolean(1) // true Boolean('0') // true Boolean('\n') // truePrimitive Wrapper ObjectsWhile primitive data types are not objects, they can exhibit object-like behavior, such as having methods and properties. This is accomplished through the use of primitive wrapper objects:

String,Number,Boolean,Symbol, andBigInt.When a property is accessed on a primitive value, JavaScript automatically wraps the value in an instance of the corresponding wrapper object. It is this temporary object on which the property access occurs. This process is often referred to as "autoboxing." Once the property is accessed, the temporary wrapper object is discarded.

For instance, the primitive string

'hello'has no methods of its own. However, when an expression like'hello'.toUpperCase()is executed, JavaScript creates a transientStringobject from the primitive and calls thetoUpperCase()method on that object.A distinction must be made between a primitive and its wrapper object. Primitive values are immutable and perform better, whereas wrapper objects are true objects. Direct instantiation of wrapper objects (e.g.,

new String('hello')) is generally discouraged as it can introduce unexpected behaviors and performance overhead. -

A

Symbolis a primitive data type that produces a unique, immutable value, which can be used as a non-string key for an object’s property.-

Symbols are created using the

Symbol()function with an optionala descriptive label, which guarantees a new, distinct symbol on every call.let id1 = Symbol() let id2 = Symbol() id1 == id2 // false let id3 = Symbol('id') let id4 = Symbol('id') id3 == id4 // false -

For creating shared symbols,

Symbol.for(key)can be used to access a global symbol registry, ensuring that for a given key, the same symbol is returned every time, whileSymbol.keyFor(symbol)takes a symbol value and returns the string key corresponding to it.let id1 = Symbol.for('id') let id2 = Symbol.for('id') id1 == id2 // true Symbol.keyFor(id1) // 'id' let id3 = Symbol('id') id1 == id3 // false Symbol.keyFor(id3) // undefined -

Symbol-keyed properties are not enumerable, meaning they are not included in

for…inloops and are ignored byJSON.stringify().const sym = Symbol() const obj = { [sym]: 'foo' } obj[sym] // 'foo' JSON.stringify(obj) // '{}'

-

1.5. Literals

Literals are fixed values, not variables, that are written directly into the source code. JavaScript supports various types of literals, including:

-

Data structures: Array and Object literals.

-

Numbers: Integer, BigInt, and Floating-point literals.

-

Text: String and Template literals.

-

Patterns: RegExp literals for regular expressions.

1.5.1. Array

An array literal is a list of zero or more expressions, each of which represents an array element, enclosed in square brackets ([]).

const coffees = ["French Roast", "Colombian", "Kona"];-

If two commas are put in a row in an array literal, the array leaves an empty slot for the unspecified element. The following example creates the

fisharray:const fish = ["Lion", /* empty */, "Angel"]; console.log(fish); // [ 'Lion', <1 empty item>, 'Angel' ]Note that the second item is "empty", which is not exactly the same as the actual

undefinedvalue. When using array-traversing methods likeArray.prototype.map, empty slots are skipped. However, index-accessingfish[1]still returnsundefined.const fish = ["Lion", /* empty */, "Angel"]; fish.map(x => console.log(x)); // Lion // Angel -

If a trailing comma is included at the end of the list of elements, the comma is ignored.

// Only the last comma is ignored. const myList = ["home", /* empty */, "school", /* empty */,];

1.5.2. Integer and BigInt

Integer and BigInt literals can be written in decimal (base 10), hexadecimal (base 16), octal (base 8) and binary (base 2).

-

A decimal integer literal is a sequence of digits without a leading

0(zero). -

A leading

0(zero) on an integer literal, or a leading0o(or0O) indicates it is in octal. -

A leading

0x(or0X) indicates a hexadecimal integer literal. -

A leading

0b(or0B) indicates a binary integer literal.A trailing nsuffix on an integer literal indicates a BigInt literal. The BigInt literal can use any of the above bases. Note that leading-zero octal syntax like0123nis not allowed, but0o123nis fine.0, 117, 123456789123456789n (decimal, base 10) 015, 0001, 0o777777777777n (octal, base 8) 0x1123, 0x00111, 0x123456789ABCDEFn (hexadecimal, "hex" or base 16) 0b11, 0b0011, 0b11101001010101010101n (binary, base 2)

1.5.3. Floating-point

A floating-point literal can have the following parts:

[digits].[digits][(E|e)[(+|-)]digits]-

An unsigned decimal integer,

-

A decimal point (

.), -

A fraction (another decimal number),

-

An exponent (

eorE).3.1415926 .123456789 -.123456789 // -0.123456789 3.1E+12 .1e-23

Note that the language specification requires numeric literals to be unsigned. Nevertheless, code fragments like -123.4 are fine, being interpreted as a unary - operator applied to the numeric literal 123.4.

|

1.5.4. Object

An object literal is a list of zero or more pairs of property names and associated values of an object, enclosed in curly braces ({}).

-

Object property names can be any string, including the empty string.

If the property name would not be a valid JavaScript identifier or number, it must be enclosed in quotes. -

Property names that are not valid identifiers must be accessed with bracket notation (

[]) instead of dot (.) notation.const unusualPropertyNames = { '': 'An empty string', '!': 'Bang!' } console.log(unusualPropertyNames.''); // SyntaxError: Unexpected string console.log(unusualPropertyNames.!); // SyntaxError: Unexpected token ! console.log(unusualPropertyNames[""]); // An empty string console.log(unusualPropertyNames["!"]); // Bang! -

Object literals support a range of shorthand syntaxes that include setting the prototype at construction, shorthand for

foo: fooassignments, defining methods, makingsupercalls, and computing property names with expressions.const obj = { // __proto__ __proto__: theProtoObj, // Shorthand for 'handler: handler' handler, // Methods toString() { // Super calls return "d " + super.toString(); }, // Computed (dynamic) property names ["prop_" + (() => 42)()]: 42, };

1.5.5. Regex

A regex literal is a pattern enclosed between slashes: /pattern/flags.

const re1 = /ab+c/; // new RegExp("ab+c");

const re2 = /\w+\s/g; // new RegExp("\\w+\\s", "g");1.5.6. String

A string literal is zero or more characters enclosed in double (") or single (') quotation marks. A string must be delimited by quotation marks of the same type (that is, either both single quotation marks, or both double quotation marks).

'foo'

"bar"

'1234'

'one line \n another line'

"Joyo's cat"

"He read \"The Cremation of Sam McGee\" by R.W. Service.";1.5.7. Template

Template literals are literals delimited with backtick (`) characters, allowing for multi-line strings, string interpolation with embedded expressions, and special constructs called tagged templates.

`string text`

`string text line 1

string text line 2`

`string text ${expression} string text`

tagFunction`string text ${expression} string text`2. Control flow and error handling

The most basic statement is a block statement, which is used to group statements, which is delimited by a pair of curly braces {}:

{

statement1;

statement2;

// …

statementN;

}2.1. Conditional statements

A conditional statement is a set of commands that executes if a specified condition is true. JavaScript supports two conditional statements: if…else and switch. The following values evaluate to false (also known as Falsy values):

-

the keyword

false -

undefined,null -

0,-0,0n -

NaN -

the empty string (

"")

All other values—including all objects—evaluate to true when passed to a conditional statement.

| A falsy (sometimes written falsey) value is a value that is considered false when encountered in a Boolean context. |

|

Note: Do not confuse the primitive boolean values For example: |

-

Use the

ifstatement to execute a statement when a logical condition istrue, the optionalelse ifto test multiple conditions in sequence, and the optionalelseclause to execute a statement if no prior conditions are met.if (condition1) { statement1; } else if (condition2) { statement2; } else if (conditionN) { statementN; } else { statementLast; } -

A

switchstatement allows a program to evaluate an expression and attempt to match the expression’s value to acaselabel. If a match is found, the program executes the associated statement.switch (expression) { case label1: statements1; break; case label2: statements2; break; // … default: statementsDefault; }

2.2. Error handling

An exception is a runtime error that has been thrown, either implicitly by the JavaScript engine (e.g., a TypeError) or explicitly by code via the throw statement—an action also known as raising an exception.

-

The standard, built-in

Errorconstructor in JavaScript creates objects that represent an error, standardizing the information through key properties such as:-

A human-readable

messageof the error, which is set when the object is created. -

A

namethat identifies the class of error (e.g.,Error,TypeError,ReferenceError). -

A widely supported (but non-standard)

stackproperty for stack traces.// Creating a new Error object const err = new Error('The resource could not be found.'); console.log(err.name); // Output: By default, its value is 'Error'. console.log(err.message); // Output: The resource could not be found.

-

-

A

throwstatement is used to raise a user-defined exception.// Any expression can be thrown. // 1. Throw a string // throw 'String Error: Something went wrong.'; // 2. Throw a number // throw 404; // 3. Throw an object literal // throw { error: 'CustomError', message: 'A custom error object.' }; // 4. Throw an instance of the Error object (Best Practice) throw new Error('This is a standard error object.');While any expression can be thrown, it is best practice to throw an instance of the Errorobject—or a more specific ECMAScript exception (e.g.,TypeError), or aDOMException—instead of primitive values like strings or numbers. -

The

try…catch…finallystatement is JavaScript’s primary mechanism for handling exceptions, consisting of atryblock, and at least one of acatchblock or afinallyblock.-

The

tryblock contains code that may throw an exception. -

The

catchblock executes if an exception is thrown, and is unconditional, but specific error types can be handled by inspecting the error object with theinstanceofoperator, and an error can be re-thrown if it is not meant to be handled in the block.try { console.log("1. Entering the try block."); throw new TypeError("This is a type error."); console.log("2. This line is never reached."); } catch (error) { console.log("3. An error was caught."); if (error instanceof TypeError) { console.log("4. Caught a TypeError:", error.message); } else { console.log("5. Not a TypeError, re-throwing..."); throw error; } } -

The

finallyblock is optional and always executes aftertryandcatch, regardless of an exception, which is used for cleanup operations.try { console.log("1. Entering the try block."); } finally { console.log("2. The finally block always executes, even without a catch."); } -

A

returnstatement within afinallyblock will override anyreturnorthrowfrom thetryandcatchblocks, becoming the definitive return value for the entire function.A function exits by either returning a value or throwing an exception, but a finallyblock executes before the function’s frame is popped from the call stack, and a return within it will swallow any pending return or exception, forcing the function to exit with the finally’s value instead.

-

3. Loops and iteration

3.1. For

-

A

forloop repeats until a specified condition evaluates to false. The JavaScript for loop is similar to the Java and Cforloop.// similar to the Java and C for loop. for (initialization; condition; afterthought) statementfor (let i = 0; i < 3; i++) { console.log(i); } // 0 // 1 // 2 -

The

for…instatement iterates a specified variable over all the enumerable properties of an object. For each distinct property, JavaScript executes the specified statements.for (variable in object) statementconst car = { make: "Ford", model: "Mustang" }; for (const p in car) { console.log(`car.${p} = ${car[p]}`); } // car.make = Ford // car.model = MustangAlthough it may be tempting to use this as a way to iterate over Array elements, the

for…instatement will return the name of the user-defined properties in addition to the numeric indexes.const nums = [3, 4, 5]; nums.foo = 'bar'; for (const idx in nums) { console.log(`nums[${idx}] = ${nums[idx]}`); } // nums[0] = 3 // nums[1] = 4 // nums[2] = 5 // nums[foo] = bar -

The

for…ofstatement creates a loop Iterating over iterable objects (includingArray,Map,Set,argumentsobject and so on), invoking a custom iteration hook with statements to be executed for the value of each distinct property.for (variable of object) statementconst nums = [3, 4, 5]; nums.foo = 'bar'; for (const num of nums) { console.log(num); } // 3 // 4 // 5 -

The

for…ofandfor…instatements can also be used with destructuring.const obj = { foo: 1, bar: 2 }; for (const [key, val] of Object.entries(obj)) { console.log(key, val); } // "foo" 1 // "bar" 2

3.2. While

-

The

whilestatement executes its statements as long as a specified condition evaluates totrue.while (condition) statementlet i = 0; while (i < 3) { console.log(i); i++; } // 0 // 1 // 2 -

The

do…whilestatement repeats until a specified condition evaluates to false.do // statement is always executed once before the condition is checked. statement while (condition);let i = 0; do { console.log(i); i++; } while(i < 3) // 0 // 1 // 2

3.3. Label, break, continue

-

A

labelprovides a statement with an identifier that lets you refer to it elsewhere in your program.label: statement -

Use the

breakstatement to terminate a loop,switch, or in conjunction with a labeled statement.-

When you use

breakwithout a label, it terminates the innermost enclosingwhile,do-while,for, orswitchimmediately and transfers control to the following statement. -

When you use

breakwith a label, it terminates the specified labeled statement.

break; break label;let x = 0; let z = 0; labelCancelLoops: while (true) { console.log("Outer loops:", x); x += 1; z = 1; while (true) { console.log("Inner loops:", z); z += 1; if (z === 10 && x === 10) { break labelCancelLoops; } else if (z === 10) { break; } } } -

-

The

continuestatement can be used to restart awhile,do-while,for, orlabelstatement.-

When you use

continuewithout a label, it terminates the current iteration of the innermost enclosingwhile,do-while, orforstatement and continues execution of the loop with the next iteration.In contrast to the

breakstatement,continuedoes not terminate the execution of the loop entirely.In a

whileloop, it jumps back to the condition.In a

forloop, it jumps to theincrement-expression. -

When you use

continuewith a label, it applies to the looping statement identified with that label.

continue; continue label;let i = 0; let j = 10; checkiandj: while (i < 4) { console.log(i); i += 1; checkj: while (j > 4) { console.log(j); j -= 1; if (j % 2 === 0) { continue checkj; } console.log(j, "is odd."); } console.log("i =", i); console.log("j =", j); } -

4. Functions

In JavaScript, functions are first-class objects, which can be passed to other functions, returned from functions, and assigned to variables and properties, and can also have properties and methods just like any other object.

4.1. Function definition

-

A function definition (also called a function declaration, or function statement) is a statement that defines a function using the

functionkeyword, a mandatoryname, a list of pass-by-value parameters in parentheses(), and a body of statements enclosed in curly braces{}.function square(number) { return number * number; } -

A function can be defined inside another (creating a nested function), which has full access to its parent function’s scope, forming a closure that is commonly used for state encapsulation and creating private variables.

function createFibonacciGenerator() { let a = 0; let b = 1; return function next() { const result = a; a = b; b = result + b; return result; }; }

-

A function can be defined as a function expression with an optional name (i.e. anonymous function).

// Anonymous function expression const square = function (number) { return number * number; }; console.log(square(4)); // 16// Named expression for recursion and debugging const factorial = function fac(n) { return n < 2 ? 1 : n * fac(n - 1); }; console.log(factorial(3)); // 6// Passed as an argument (a callback) const nums = [1, 3, 5]; const squares = nums.map(function (num) { return num * num; }); console.log(squares.join()); // 1,9,25A Named Function Expression (NFE) is a function expression that includes a name.

const myFunction = function myInternalName() { // function body }; console.log(myFunction.name) // myInternalName-

The function is assigned to a variable (e.g.,

myFunction), which is used to invoke it. -

The function’s own name (e.g.,

myInternalName) is only accessible within its body for self-referencing (e.g., recursion), and also appears in debugger stack traces, making it easier to identify the source of errors compared to an anonymous function.

-

4.2. Arrow functions

-

An arrow function expression is a syntactically compact alternative to a traditional function expression that does not have its own bindings to

this,arguments,new.targetorsuper, and cannot be used as a constructor, method or a generator.const materials = ['Hydrogen', 'Helium', 'Lithium']; // Traditional function expression const lengths = materials.map(function(material) { return material.length; }); console.log(lengths); // [8, 6, 7] // Arrow function equivalent const arrowLengths = materials.map(material => material.length); console.log(arrowLengths); // [8, 6, 7] -

In arrow functions,

thisis lexically inherited from the enclosing scope, while in traditional function expressions, it is dynamically bound depending on the call context (such as the object it’s called on, the global object, or a new instance when used withnew).const myObject = { name: 'MyObject', // Method using a traditional function traditionalMethod: function() { console.log('Outer this:', this.name); // Logs "MyObject" setTimeout(function() { // `this` is dynamically bound to the global object (or undefined in strict mode) // because setTimeout is a global function. console.log('Inner (traditional):', this.name); // Logs "undefined" }, 100); }, // Method using an arrow function for the callback arrowMethod: function() { console.log('Outer this:', this.name); // Logs "MyObject" setTimeout(() => { // `this` is lexically inherited from the enclosing `arrowMethod` scope, // so it still refers to myObject. console.log('Inner (arrow):', this.name); // Logs "MyObject" }, 200); } }; myObject.traditionalMethod(); myObject.arrowMethod();

4.3. Function object

-

The Function object is the built-in constructor for all functions, meaning every declared or expressed function is an instance of this object.

-

The

Functionconstructor can creates functions from strings at runtime (a discouraged practice) that are insecure (likeeval()) and execute only in the global scope, without closures.// The first arguments are the parameter names for the new function. // The last argument is the string of code for the function body. const sum = new Function('a', 'b', 'return a + b'); const result = sum(10, 5); console.log(result); // 15(function() { const localValue = 'local'; globalThis.globalValue = 'global'; // This function will succeed in logging the global variable, // but throw an error when it tries to access the local one. const dynamicFunc = new Function('console.log(globalValue); console.log(localValue);'); try { dynamicFunc(); } catch (e) { console.error(`Error: ${e.message}`); // Error: localValue is not defined } })(); -

The

call(),apply(), andbind()are the most important methods inherited fromFunction.prototypethat provide explicit control over a function’sthiscontext.-

The

call()method executes a function with a giventhisvalue and arguments provided individually:function.call(thisArg, arg1, arg2, …).const person = { name: 'Sarah' }; function introduce(greeting, punctuation) { console.log(`${greeting}, my name is ${this.name}${punctuation}`); } // The first argument sets `this` to `person`. // Subsequent arguments are passed directly to the function. introduce.call(person, 'Hello', '!'); // Output: Hello, my name is Sarah! -

The

apply()method is nearly identical tocall(), but it accepts the function’s arguments as a single array:function.apply(thisArg, [argsArray]).const person = { name: 'John' }; function introduce(greeting, punctuation) { console.log(`${greeting}, my name is ${this.name}${punctuation}`); } // The first argument sets `this`. // The second argument is an array of arguments for the function. introduce.apply(person, ['Hi', '.']); // Output: Hi, my name is John. -

The

bind()method creates and returns a new function with a permanently boundthisvalue and optional, pre-set initial arguments:function.bind(thisArg, arg1, arg2, …).const person = { name: 'Maria' }; function introduce(greeting, punctuation) { console.log(`${greeting}, my name is ${this.name}${punctuation}`); } // `bind()` returns a new function with `this` permanently set to `person`. const introduceMaria = introduce.bind(person, 'Greetings'); // We can call this new function later, providing any remaining arguments. introduceMaria('!!'); // Output: Greetings, my name is Maria!!

-

4.4. Arguments object

-

The

argumentsobject is an array-like object accessible inside traditional (non-arrow) functions that contains the value of every argument passed to that function.The

argumentsobject is a local variable available inside a function, while theFunction.prototype.argumentsproperty was a non-standard, deprecated property on the function object itself.-

The

argumentsobject is array-like, meaning it has alengthproperty and indexed elements, but doesn’t possess all of the array-manipulation methods likemap()orforEach(). -

The

argumentsobject is considered a legacy feature, and modern best practice is to use rest parameters (…args), which provide a true array of arguments.function traditionalSum() { // 'arguments' is an array-like object, not a real array. console.log(Array.isArray(arguments)); // false let total = 0; // We can still iterate over it with a for loop. for (let i = 0; i < arguments.length; i++) { total += arguments[i]; } return total; } console.log(traditionalSum(1, 2, 3, 4)); // 10 // The modern and preferred approach using rest parameters function modernSum(...numbers) { // 'numbers' is a real array. console.log(Array.isArray(numbers)); // true // We can use powerful array methods like reduce(). return numbers.reduce((total, num) => total + num, 0); } console.log(modernSum(1, 2, 3, 4)); // 10

-

4.5. Default parameters and rest parameters

-

In JavaScript, default parameters can be used to set specific initial values, instead of

undefinedwhen no argument is provided.// function multiply(a, b) { // b = typeof b !== "undefined" ? b : 1; // return a * b; // } // With default parameters, a manual check in the function body is no longer necessary. function multiply(a, b = 1) { return a * b; } console.log(multiply(5)); // 5 -

The spread syntax can be used to expand an iterable into individual elements in contexts like array literals, function calls, or object literals.

const arr1 = [1, 2]; const arr2 = [3, 4]; const obj1 = { a: 1, b: 2 }; const obj2 = { c: 3, d: 4 }; // 1. In Array Literals: Combine arrays or insert elements const combinedArray = [...arr1, 0, ...arr2]; console.log(combinedArray); // [1, 2, 0, 3, 4] // 2. In Function Calls: Pass array elements as separate arguments function sum(x, y, z) { return x + y + z; } const numbers = [10, 20, 30]; console.log(sum(...numbers)); // 60 // 3. In Object Literals: Combine objects or add properties const combinedObject = { ...obj1, e: 5, ...obj2 }; console.log(combinedObject); // { a: 1, b: 2, c: 3, d: 4, e: 5 } -

The rest parameter syntax allows a function to accept an indefinite number of arguments as an array, providing a way to represent variadic) functions in JavaScript.

function multiply(multiplier, ...theArgs) { return theArgs.map((x) => multiplier * x); } const arr = multiply(2, 1, 2, 3); console.log(arr); // [2, 4, 6]

4.6. Recursion and closures

-

A recursive function is a function that calls itself from within its own body, either by its name or by using an in-scope variable that refers to the function.

// Example 1: Using a named function declaration function countDown(n) { // Base case: The condition that stops the recursion. if (n <= 0) { console.log("Lift off!"); return; } console.log(n); // Recursive call: The function calls itself with a modified argument. countDown(n - 1); } console.log("--- Calling by function name ---"); countDown(3);// Example 2: Using a variable that refers to the function const factorial = function(n) { // Base case if (n <= 1) { return 1; } // Recursive call: The function calls itself using the `factorial` variable. return n * factorial(n - 1); }; console.log("\\n--- Calling by variable reference ---"); console.log(`Factorial of 5 is: ${factorial(5)}`); -

A closure is a function that retains access to its lexical environment (including variables from its outer scope) even when executed outside that outer scope.

A lexical environment (or lexical scope) is a fundamental programming concept where the scope of a variable is determined by where it is written in the source code (statically), not where it is called, which is common in modern languages, ensuring predictable variable access.

In JavaScript, each lexical environment holds its local variables and a reference to its parent’s environment, forming a scope chain that JavaScript traverses to resolve identifiers.

-

JavaScript first attempts to resolve the variable in the current (local) lexical environment.

-

If not found there, it then checks the outer (parent) lexical environment.

-

This process continues up the scope chain until the global lexical environment is reached.

-

If the variable is still not found in the global environment, a

ReferenceErroris thrown.

const globalVar = 'I am global'; // Part of the Global Lexical Environment function outerFunction() { const outerVar = 'I am in outerFunction'; // Part of outerFunction's Lexical Environment function innerFunction() { const innerVar = 'I am in innerFunction'; // Part of innerFunction's Lexical Environment console.log(innerVar); // Found in innerFunction's Environment Record console.log(outerVar); // Not in innerFunction, found by following Outer Environment Reference to outerFunction console.log(globalVar); // Not in innerFunction or outerFunction, found by following Outer Environment Reference to Global // console.log(nonExistentVar); // Would cause a ReferenceError after checking all environments } innerFunction(); } outerFunction();-

A closure is typically created with a nested function that captures variables from its enclosing function’s lexical environment.

function makeCounter() { let count = 0; return function() { // This is the closure count++; return count; }; } const counter1 = makeCounter(); const counter2 = makeCounter(); // Creates a separate closure with its own 'count' console.log(counter1()); // Output: 1 console.log(counter2()); // Output: 1 (demonstrates independence) console.log(counter1()); // Output: 2 (demonstrates state retention) -

A common closure mistake occurs when functions created in for loops using var-based index.

-

Because

varis function or global-scoped, all functions created in the loop close over the sameivariable, leading to unexpected results.for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) { // var-based index setTimeout(function() { console.log(i); // Always logs 3, 3, 3 }, 100 * i); } -

The block-scoped

letorconst, which create a new binding for each iteration, ensures closures capture the correct value.for (let i = 0; i < 3; i++) { // let-based index setTimeout(function() { console.log(i); // Logs 0, 1, 2 }, 100 * i); }for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) { let j = i; // a new block-scoped var setTimeout(function() { console.log(j); // Logs 0, 1, 2 }, 100 * j); }

-

-

5. Expressions and operators

Expressions and operators are the building blocks of JavaScript computations, with expressions combining values and operators to yield results, and operators performing specific actions on operands.

operand1 operator operand2 // infix binary operator, e.g., 3 + 4 or x * y

operator operand // prefix unary operator, e.g., ++x

operand operator // postfix unary operator, e.g., x++5.1. Assignment operators

An assignment operator assigns a value to its left operand based on the value of its right operand. The simple assignment operator is equal (=), which assigns the value of its right operand to its left operand. There are also compound assignment operators that are shorthand for the operations.

x = f() // x = f()

x += f() // x = x + f()

x -= f() // x = x - f()

x *= f() // x = x * f()

x /= f() // x = x / f()

x %= f() // x = x % f()

x **= f() // x = x ** f()

x <<= f() // x = x << f()

x >>= f() // x = x >> f()

x >>>= f() // x = x >>> f()

x &= f() // x = x & f()

x ^= f() // x = x ^ f()

x |= f() // x = x | f()

x &&= f() // x && (x = f())

x ||= f() // x || (x = f())

x ??= f() // x ?? (x = f())5.1.1. Assigning to properties

-

If an expression evaluates to an object, then the left-hand side of an assignment expression may make assignments to properties of that expression.

const obj = {}; obj.x = 3; console.log(obj.x); // Prints 3. console.log(obj); // Prints { x: 3 }. const key = "y"; obj[key] = 5; console.log(obj[key]); // Prints 5. console.log(obj); // Prints { x: 3, y: 5 }. -

If an expression does not evaluate to an object, then assignments to properties of that expression do not assign:

const val = 0; val.x = 3; console.log(val.x); // Prints undefined. console.log(val); // Prints 0.In strict mode, the code above throws, because one cannot assign properties to primitives.

"use strict" const val = 0; val.x = 3; // Uncaught TypeError: can't assign to property "x" on 0: not an object

5.1.2. Destructuring

The destructuring assignment syntax is a JavaScript expression that makes it possible to extract data from arrays or objects or any iterable using a syntax that mirrors the construction of array and object literals.

-

Without destructuring, it takes multiple statements to extract values from arrays and objects:

// For arrays const foo = ["one", "two", "three"]; const one = foo[0]; const two = foo[1]; const three = foo[2];// For objects const person = { firstName: 'John', lastName: 'Doe' }; const firstName = person.firstName; const lastName = person.lastName; -

With destructuring, multiple values can be extracted into distinct variables using a single statement:

// For arrays const [one, two, three] = foo;// For objects const { firstName, lastName } = person; -

A comma can be used to skip over a value in an iterable without assigning them to a variable.

const [one, , three] = foo; -

The rest pattern (

…) collects the remaining elements of an iterable into a new array or the remaining own-enumerable properties of an object into a new object.// For arrays const scores = [98, 85, 77, 65, 54]; const [winner, ...others] = scores; console.log(winner); // 98 console.log(others); // [85, 77, 65, 54]// For objects const settings = { theme: "dark", fontSize: 14, showSidebar: true }; const { theme, ...otherSettings } = settings; console.log(theme); // "dark" console.log(otherSettings); // { fontSize: 14, showSidebar: true } -

When destructuring, a variable is assigned undefined if its corresponding element or property is missing or

undefined, unless a default value is provided.const source = [10, 20]; // Destructuring with three different types of default values: // d: A literal number. // e: An Immediately Invoked Function Expression (IIFE). // f: A standard function definition. const [a, b, c, d = 40, e = (() => a + b)(), f = () => a + b] = source; // a and b are assigned directly from the `source` array. console.log(a); // 10 console.log(b); // 20 // c is undefined because the `source` array has no third element. console.log(c); // undefined // d is assigned its literal default value as no corresponding element was found. console.log(d); // 40 // e holds the *return value* of the IIFE, which was executed during the assignment. console.log(e); // 30 // f holds the function definition itself; it has not been executed yet. console.log(f); // [Function: f] // To get the value from f, the function must be invoked here. console.log(f()); // 30 -

Destructuring can be used in function parameters to unpack values from arrays or properties from objects.

const userProfile = ['John', 'Doe']; function printName([firstName, lastName]) { console.log(`Name: ${firstName} ${lastName}`); } printName(userProfile); // Name: John Doeconst person = { name: 'Alice', age: 30 }; function greet({ name }) { console.log(`Hello, ${name}!`); } greet(person); // Hello, Alice!

5.1.3. Evaluation and nesting

In general, assignments are used within a variable declaration (i.e., with const, let, or var) or as standalone statements.

// Declares a variable x and initializes it to the result of f().

// The result of the x = f() assignment expression is discarded.

let x = f();

x = g(); // Reassigns the variable x to the result of g().However, like other expressions, assignment expressions like x = f() evaluate into a result value. Although this result value is usually not used, it can then be used by another expression.

By chaining or nesting an assignment expression, its result can itself be assigned to another variable. It can be logged, it can be put inside an array literal or function call, and so on.

let x;

const y = (x = f()); // Or equivalently: const y = x = f();

console.log(y); // Logs the return value of the assignment x = f().

console.log(x = f()); // Logs the return value directly.

// An assignment expression can be nested in any place

// where expressions are generally allowed,

// such as array literals' elements or as function calls' arguments.

console.log([0, x = f(), 0]);

console.log(f(0, x = f(), 0));Avoid assignment chains

Chaining assignments or nesting assignments in other expressions can result in surprising behavior. For this reason, chaining assignments in the same statement is discouraged.

In particular, putting a variable chain in a const, let, or var statement often does not work. Only the outermost/leftmost variable would get declared; other variables within the assignment chain are not declared by the const/let/var statement.

const z = y = x = f();This statement seemingly declares the variables x, y, and z. However, it only actually declares the variable z. y and x are either invalid references to nonexistent variables (in strict mode) or, worse, would implicitly create global variables for x and y in sloppy mode.

// "use strict"

{ const z = y = x = Math.PI; }

console.log(x, y); // 3.141592653589793 3.141592653589793

console.log(z); // Uncaught ReferenceError: z is not defined"use strict"

{ const z = y = x = Math.PI; } // Uncaught ReferenceError: assignment to undeclared variable x5.2. Comparison operators

-

The strict equality operator (

===)checks for equality in both value and type, returning aBooleanresult, while the loose equality operator (==) performs type conversion before comparing only the values. See also Object.is and sameness in JS.console.log(1 === 1); // Expected output: true console.log('hello' === 'hello'); // Expected output: true console.log('1' === 1); // Expected output: false console.log(0 === false); // Expected output: falseconsole.log(1 == 1); // Expected output: true console.log('hello' == 'hello'); // Expected output: true console.log('1' == 1); // Expected output: true console.log(0 == false); // Expected output: true -

The strict inequality operator (

!==) checks for inequality in either value or type, returning aBooleanresult, while the loose inequality operator (!=) performs type conversion before comparing only the values.console.log(1 !== 1); // Expected output: false console.log('hello' !== 'hello'); // Expected output: false console.log('1' !== 1); // Expected output: true console.log(0 !== false); // Expected output: trueconsole.log(1 != 1); // Expected output: false console.log('hello' != 'hello'); // Expected output: false console.log('1' != 1); // Expected output: false console.log(0 != false); // Expected output: false

5.3. Arithmetic operators

In addition to the standard arithmetic operations (+, -, *, /), JavaScript provides also the arithmetic operators: %, ++, --, -, +, **.

| division by zero produces Infinity. |

1 / 0 // Infinity

-1 / 0 // -Infinity

5 % 2 // 1

5 ** 2 // 25

+0 // 0

-0 // -0

+1 // 1

-1 // -1

+true // 1

-true // -1

+'' // 0

-'' // -05.4. Bitwise operators

A bitwise operator treats their operands as a set of 32 bits (zeros and ones), rather than as decimal, hexadecimal, or octal numbers.

-

&,|,^,~,<<,>>,>>> -

The operands are converted to thirty-two-bit integers and expressed by a series of bits (zeros and ones). Numbers with more than 32 bits get their most significant bits discarded. For example, the following integer with more than 32 bits will be converted to a 32-bit integer:

Before: 1110 0110 1111 1010 0000 0000 0000 0110 0000 0000 0001 After: 1010 0000 0000 0000 0110 0000 0000 0001 -

The bitwise shift operators take two operands: the first is a quantity to be shifted, and the second specifies the number of bit positions by which the first operand is to be shifted. The direction of the shift operation is controlled by the operator used.

-

Shift operators convert their operands to thirty-two-bit integers and return a result of either type

NumberorBigInt: specifically, if the type of the left operand isBigInt, they returnBigInt; otherwise, they returnNumber.

5.5. Logical operators

-

Logical operators are typically used with Boolean (logical) values; when they are, they return a Boolean value.

-

The

&&and||operators actually return the value of one of the specified operands, so if these operators are used with non-Boolean values, they may return a non-Boolean value.const a1 = true && true; // t && t returns true const a2 = true && false; // t && f returns false const a3 = false && true; // f && t returns false const a4 = false && false; // f && f returns false const a5 = true && "Dog"; // t && t returns Dog const a6 = false && "Dog"; // f && t returns falseconst o1 = true || true; // t || t returns true const o2 = false || true; // f || t returns true const o3 = true || false; // t || f returns true const o4 = false || false; // f || f returns false const o5 = "Cat" || true; // t || t returns Cat const o6 = "Cat" || false; // t || f returns Cat const o7 = false || "Cat"; // f || t returns Cat -

As logical expressions are evaluated left to right, they are tested for possible "short-circuit" evaluation using the following rules:

-

false && anythingis short-circuit evaluated to false. -

true || anythingis short-circuit evaluated to true.

-

-

The nullish coalescing (

??) operator is a logical operator that returns its right-hand side operand when its left-hand side operand isnullorundefined, and otherwise returns its left-hand side operand.const foo = null ?? 'default string'; console.log(foo); // Expected output: "default string" const baz = 0 ?? 42; console.log(baz); // Expected output: 0

5.6. Conditional (ternary) operator

The conditional operator is the only JavaScript operator that takes three operands. The operator can have one of two values based on a condition. The syntax is:

condition ? val1 : val25.7. Comma operator

The comma operator (,) evaluates both of its operands and returns the value of the last operand.

-

This operator is primarily used inside a for loop, to allow multiple variables to be updated each time through the loop.

-

It is regarded bad style to use it elsewhere, when it is not necessary. Often two separate statements can and should be used instead.

const x = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9];

const a = [x, x, x, x, x];

for (let i = 0, j = 9; i <= j; i++, j--) {

// ^

console.log(`a[${i}][${j}]= ${a[i][j]}`);

}5.8. Unary operators

-

The

deleteoperator removes a property from an object. If the property’s value is an object and there are no more references to the object, the object held by that property is eventually released automatically.delete object.property delete object[property]const car = { make: "Ford", model: "Mustang" }; delete car.make; console.log(car); // { model: "Mustang" }const nums = [0, 1, 2, 3]; delete nums[1]; console.log(nums); // [ 0, <1 empty slot>, 2, 3 ] -

The

typeofoperator returns a string indicating the type of the unevaluated operand. operand is the string, variable, keyword, or object for which the type is to be returned. The parentheses are optional.typeof new Function("5 + 2"); // "function" typeof "round"; // "string" typeof 1; // "number" typeof ["Apple", "Mango", "Orange"]; // "object" typeof new Date(); // "object" typeof true; // "boolean" typeof {}; // "boolean" typeof /ab+c/; // "object" typeof undefined; // "undefined" typeof null; // "object" -

The

voidoperator specifies an expression to be evaluated without returning a value.expressionis a JavaScript expression to evaluate. The parentheses surrounding the expression are optional, but it is good style to use them to avoid precedence issues.const output = void 1; console.log(output); // Expected output: undefined void console.log('expression evaluated'); // Expected output: "expression evaluated" void (function iife() { console.log('iife is executed'); })(); // Expected output: "iife is executed" void function test() { console.log('test function executed'); }; try { test(); } catch (e) { console.log('test function is not defined'); // Expected output: "test function is not defined" }

5.9. Relational operators

-

The

inoperator returnstrueif the specified property is in the specified object or its prototype chain. Theinoperator cannot be used to search for values in other collections. To test if a certain value exists in an array, useArray.prototype.includes(). For sets, useSet.prototype.has().// Arrays const trees = ["redwood", "bay", "cedar", "oak", "maple"]; 0 in trees; // returns true 3 in trees; // returns true 6 in trees; // returns false "bay" in trees; // returns false // (you must specify the index number, not the value at that index) "length" in trees; // returns true (length is an Array property) // built-in objects "PI" in Math; // returns true const myString = new String("coral"); "length" in myString; // returns true // Custom objects const mycar = { make: "Honda", model: "Accord", year: 1998 }; "make" in mycar; // returns true "model" in mycar; // returns true -

The

instanceofoperator tests to see if the prototype property of a constructor appears anywhere in the prototype chain of an object. The return value is a boolean value. Its behavior can be customized withSymbol.hasInstance.function Car(make, model, year) { this.make = make; this.model = model; this.year = year; } const auto = new Car('Honda', 'Accord', 1998); console.log(auto instanceof Car); // Expected output: true console.log(auto instanceof Object); // Expected output: true

5.10. Grouping operator

The grouping ( ) operator controls the precedence of evaluation in expressions. It also acts as a container for arbitrary expressions in certain syntactic constructs, where ambiguity or syntax errors would otherwise occur.

-

Evaluating addition and subtraction before multiplication and division.

const a = 1; const b = 2; const c = 3; // default precedence a + b * c; // 7 // evaluated by default like this a + (b * c); // 7 // now overriding precedence // addition before multiplication (a + b) * c; // 9 // which is equivalent to a * c + b * c; // 9 -

Using the grouping operator to eliminate parsing ambiguity

// An IIFE (Immediately Invoked Function Expression) (function () { // code })();// an arrow function expression body const f = () => ({ a: 1 });// a property accessor dot `.` may be ambiguous with a decimal point (1).toString(); // "1"

5.11. Optional chaining operator

The optional chaining (?.) operator accesses an object’s property or calls a function. If the object accessed or function called using this operator is undefined or null, the expression short circuits and evaluates to undefined instead of throwing an error.

const adventurer = {

name: 'Alice',

cat: {

name: 'Dinah',

},

};

const dogName = adventurer.dog?.name;

console.log(dogName);

// Expected output: undefined

console.log(adventurer.someNonExistentMethod?.());

// Expected output: undefined6. Regular expressions

-

Regular expression literals (

/pattern/flags) provide compilation of the regular expression when the script is loaded. If the regular expression remains constant, using this can improve performance.const re = /ab+c/i; // literal notation -

Using the RegExp constructor function provides runtime compilation of the regular expression.

// OR const re = new RegExp("ab+c", "i"); // constructor with string pattern as first argument // OR const re = new RegExp(/ab+c/, "i"); // constructor with regular expression literal as first argument -

Regular expressions are used with the

RegExpmethodstest()andexec()and with theStringmethodsmatch(),matchAll(),replace(),replaceAll(),search(), andsplit().

7. Indexed and keyed Collections

Indexed collections (data which are ordered by an index value) includes arrays and array-like constructs such as Array objects and TypedArray objects.

7.1. Arrays

JavaScript arrays are a specialized type of object. At the implementation level, array elements are stored as standard object properties, using the string representation of the array index as the property key. For example, the element at index 0 is stored under the key '0'.

const nums = []; // same as: const nums = new Array(); OR const nums = new Array(0);

nums[0] = 0; // nums['0'] = 0;

nums[2] = 2;

nums.size = function () { return this.length; }; // a user-defined extension method

console.log(nums); // Array(3) [ 0, <1 empty slot>, 2 ]

console.log(nums.length, nums.size()); // 3 3

nums.length = 2;

console.log(nums); // Array [ 0, <1 empty slot> ]-

The

push()andpop()methods add and remove elements from the end of an array, respectively, while theunshift()andshift()methods add and remove elements from the beginning.// --- Basic push() and pop() --- const arr1 = [10, 20]; arr1.push(30); // Add to end console.log(arr1); // [10, 20, 30] arr1.pop(); // Remove from end console.log(arr1); // [10, 20] // --- Basic shift() and unshift() --- const arr2 = [10, 20]; arr2.unshift(0); // Add to start console.log(arr2); // [0, 10, 20] arr2.shift(); // Remove from start console.log(arr2); // [10, 20] // --- Using spread syntax to add multiple items --- const source = [3, 4]; const pushTarget = [1, 2]; // Add all items from 'source' to the end pushTarget.push(...source); console.log(pushTarget); // [1, 2, 3, 4] const unshiftTarget = [1, 2]; // Add all items from 'source' to the beginning unshiftTarget.unshift(...source); console.log(unshiftTarget); // [3, 4, 1, 2] -

The

concat()method creates a new array by joining the source array with other arrays and/or values.const arr1 = ['a', 'b']; const arr2 = ['c', 'd']; // Join two arrays const result1 = arr1.concat(arr2); console.log(result1); // ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] // Join an array with additional values const result2 = arr1.concat('c', 'd'); console.log(result2); // ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] // The original arrays are not changed console.log(arr1); // ['a', 'b'] console.log(arr2); // ['c', 'd'] -

The

splice()method changes an array by removing, replacing, or adding elements in place, and returns an array of the deleted elements.const months = ['Jan', 'March', 'April', 'June']; // At index 1, delete 0 elements, then insert 'Feb'. months.splice(1, 0, 'Feb'); console.log(months); // ["Jan", "Feb", "March", "April", "June"] // At index 3, delete 1 element. const removedItem = months.splice(3, 1); console.log(months); // ["Jan", "Feb", "March", "June"] console.log(removedItem); // ["April"] // At index 3, delete 1 element and insert 'May'. months.splice(3, 1, 'May'); console.log(months); // ["Jan", "Feb", "March", "May"] -

The

slice()method returns a new array containing a shallow copy of a portion of the original array.const animals = ['ant', 'bison', 'camel', 'duck', 'elephant']; const middle = animals.slice(1, 4); console.log(middle); // ["bison", "camel", "duck"] -

The traditional

forloop is an interruptible, index-based loop, and thefor…ofloop is an interruptible, value-based loop, while theforEach()method is an unstoppable callback.const colors = ["red", /* empty */, "green", "blue"]; // Traditional 'for' loop (visits the empty slot) console.log('--- for ---'); for (let i = 0; i < colors.length; i++) { console.log(colors[i]); } // Output: // 'red' // undefined // 'green' // 'blue' // 'for...of' and 'forEach()' (skip the empty slot) console.log('--- for...of / forEach ---'); for (const color of colors) { console.log(color); // 'red', 'green', 'blue' } colors.forEach(color => console.log(color)); // 'red', 'green', 'blue' -

The

find()method returns the first element that satisfies the provided testing function, whilefindIndex()returns that element’s index (or-1if not found).const numbers = [5, 12, 8, 130, 44]; const found = numbers.find(num => num > 10); console.log(found); // 12 const foundIndex = numbers.findIndex(num => num > 10); console.log(foundIndex); // 1 -

The

indexOf()method returns the first index (or-1if not found) of a given element, using strict equality (===) for comparison, whilelastIndexOf()returns the last index.const beasts = ['ant', 'bison', 'camel', 'duck', 'bison']; console.log(beasts.indexOf('bison')); // 1 console.log(beasts.lastIndexOf('bison')); // 4 -

The

includes()method checks if an array contains a specific value using strict equality (===), returningtrueorfalse.const pets = ['cat', 'dog', 'bat']; console.log(pets.includes('cat')); // true console.log(pets.includes('at')); // false -

The

filter()method returns a new array containing all elements for which the provided callback function returns a truthy value.const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; const evens = numbers.filter(num => num % 2 === 0); console.log(evens); // [2, 4] -

The

flat()method returns a new array with all sub-array elements concatenated into it recursively up to the specified depth.const arr = [0, 1, [2, [3, [4, 5]]]]; console.log(arr.flat()); // [ 0, 1, 2, [ 3, [ 4, 5 ] ] ] console.log(arr.flat(2)); // [ 0, 1, 2, 3, [ 4, 5 ] ] console.log(arr.flat(3)); // [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ] -

The

map()method returns a new array of the return value from executing callback on every array item.const a1 = ["a", "b", "c"]; const a2 = a1.map(x => x.toUpperCase()) console.log(a2); // [ 'A', 'B', 'C' ] -

The

flatMap()method runsmap()followed by aflat()of depth 1.const a1 = ["a", "b", "c"]; const a2 = a1.flatMap((item) => [item.toUpperCase(), item.toLowerCase()]); console.log(a2); // ['A', 'a', 'B', 'b', 'C', 'c'] -

The

reduce()method of Array instances executes a user-supplied "reducer" callback function on each element of the array, in order, passing in the return value from the calculation on the preceding element.-

The final result of running the reducer across all elements of the array is a single value.

-

The first time that the callback is run there is no "return value of the previous calculation".

-

If supplied, an initial value may be used in its place.

-

Otherwise the array element at index 0 is used as the initial value and iteration starts from the next element (index 1 instead of index 0).

-

const array1 = [1, 2, 3, 4]; // 0 + 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 const initialValue = 0; const sumWithInitial = array1.reduce( (accumulator, currentValue) => accumulator + currentValue, initialValue, ); console.log(sumWithInitial); // Expected output: 10 -

-

The

sort()method sorts an array in place, by default based on string conversion in lexicographical, while thereverse()method reverses the order of the elements in place.const numbers = [1, 10, 2, 21]; numbers.sort(); console.log(numbers); // [1, 10, 2, 21] // A compare function fixes this for numbers numbers.sort((a, b) => a - b); console.log(numbers); // [1, 2, 10, 21] numbers.reverse(); console.log(numbers); // [21, 10, 2, 1] -

The

split()method splits a string into an array, while thejoin()method joins array elements into a string.const newString = 'Hello World'; const newArray = newString.split(' '); console.log(newArray); // ["Hello", "World"] const elements = ['Fire', 'Air', 'Water']; const joinedString = elements.join(', '); console.log(joinedString); // "Fire, Air, Water" -

The

Array.isArray()static method determines whether the passed value is an Array.console.log(Array.isArray([1, 3, 5])); // Expected output: true console.log(Array.isArray('[]')); // Expected output: false console.log(Array.isArray(new Array(5))); // Expected output: true console.log(Array.isArray(new Int16Array([15, 33]))); // Expected output: false

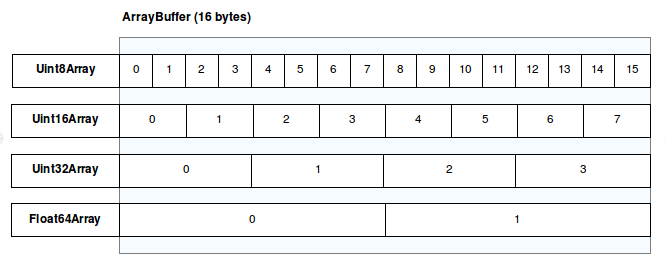

7.2. Typed arrays

JavaScript typed arrays are array-like objects that provide a mechanism for reading and writing raw binary data in memory buffers.

To achieve maximum flexibility and efficiency, JavaScript typed arrays split the implementation into buffers and views.

-

A buffer is an object representing a chunk of data; it has no format to speak of, and offers no mechanism for accessing its contents.

-

In order to access the memory contained in a buffer, it’s needed to use a view which provides a context — that is, a data type, starting offset, and number of elements.

7.3. Maps and sets

Maps and sets are keyed collections (data which are indexed by a key), and both contain elements which are iterable in the order of insertion.

|

JavaScript

|

-

A

Mapobject is a simple key/value map where the key can be any type and can iterate its elements in insertion order.// Create a new Map and initialize with some data const myMap = new Map([ ['name', 'Alice'], ['age', 30], ['city', 'New York'] ]); // 1. set(): Add more key-value pairs (keys can be any type) myMap.set(true, 'boolean key'); const objKey = { id: 1 }; myMap.set(objKey, 'object as key'); // Using an object as a key console.log('--- Map after setting values ---'); console.log('Map size:', myMap.size); // Output: 5 // 2. get(): Retrieve values by key console.log('Value for "name":', myMap.get('name')); console.log('Value for true:', myMap.get(true)); console.log('Value for objKey:', myMap.get(objKey)); console.log('Value for non-existent key:', myMap.get('country')); // Output: undefined // 3. has(): Check if a key exists console.log('Has "name"?', myMap.has('name')); // Output: true console.log('Has "country"?', myMap.has('country')); // Output: false // 4. Iteration (all in insertion order) console.log('\n--- Iterating Map entries (default for...of) ---'); for (const [key, value] of myMap) { console.log(`Key: ${key}, Value: ${value}`); } console.log('\n--- Iterating Map keys() ---'); for (const key of myMap.keys()) { console.log(`Key: ${key}`); } console.log('\n--- Iterating Map values() ---'); for (const value of myMap.values()) { console.log(`Value: ${value}`); } console.log('\n--- Iterating Map entries() explicitly ---'); for (const [key, value] of myMap.entries()) { console.log(`Entry: ${key}: ${value}`); } // 5. delete(): Remove a key-value pair myMap.delete('age'); console.log('\n--- Map after deleting key "age" ---'); console.log('Map size:', myMap.size); // Output: 4 console.log('Has "age"?', myMap.has('age')); // Output: false // 6. clear(): Remove all key-value pairs myMap.clear(); console.log('\n--- Map after clearing ---'); console.log('Map size:', myMap.size); // Output: 0 console.log('Is Map empty?', myMap.size === 0); // Output: trueIt’s important to note that the bracket notation (

myMap[key]) on aMapobject bypasses its key-value store, treating it as a plain JavaScript object for adding, accessing, or deleting regular properties that are distinct from the Map’s entries. -

A

Mapcan be also created fromObject.entries()(an iterable of string-keyed[key, value]pairs), while an iterable of[key, value]pairs (such as the output ofObject.entries()or aMap) can be transformed back into an object usingObject.fromEntries().const obj = { 'foo': 'bar', 'bar': 'buz' }; // Object.entries(): Converts an object to an array of [key, value] pairs const entries = Object.entries(obj); console.log('Object.entries(obj):', entries); // Expected output: [ [ 'foo', 'bar' ], [ 'bar', 'buz' ] ] // Creating a Map from the entries array const myMap = new Map(entries); console.log('new Map(Object.entries(obj)):', myMap); // Expected output: Map(2) { 'foo' => 'bar', 'bar' => 'buz' } // Object.fromEntries(): Transforms an array of [key, value] pairs back to an object const obj2 = Object.fromEntries(entries); console.log('Object.fromEntries(entries):', obj2); // Expected output: { foo: 'bar', bar: 'buz' } -

A

Setobject is a collection of unique values, where each value can be of any type, and its elements can be iterated in insertion order.// Create a new Set const mySet = new Set(); // 1. add(): Add values to the Set (duplicates are ignored) mySet.add('apple'); mySet.add('banana'); mySet.add('cherry'); mySet.add('apple'); // This 'apple' will be ignored as it's a duplicate const objValue = { id: 1 }; mySet.add(objValue); // Objects are unique by reference mySet.add({ id: 1 }); // This is a different object reference, so it's added console.log('--- Set after adding values ---'); console.log('Set size:', mySet.size); // 2. has(): Check if a value exists console.log('Has "apple"?', mySet.has('apple')); console.log('Has "grape"?', mySet.has('grape')); console.log('Has objValue?', mySet.has(objValue)); console.log('Has {id:1} (new object)?', mySet.has({ id: 1 })); // 3. Iteration (all in insertion order) console.log('\n--- Iterating Set directly (default for...of) ---'); for (const value of mySet) { console.log(`Value: ${value}`); } console.log('\n--- Iterating Set keys() (returns values) ---'); for (const key of mySet.keys()) { // For Set, keys() returns the values console.log(`Key (value): ${key}`); } console.log('\n--- Iterating Set values() (alias for keys()) ---'); for (const value of mySet.values()) { console.log(`Value: ${value}`); } console.log('\n--- Iterating Set entries() (returns [value, value] pairs) ---'); for (const entry of mySet.entries()) { // For Set, entries() returns [value, value] console.log(`Entry: ${entry}`); } // 4. delete(): Remove a value mySet.delete('banana'); console.log('\n--- Set after deleting "banana" ---'); console.log('Set size:', mySet.size); console.log('Has "banana"?', mySet.has('banana')); // 5. clear(): Remove all values mySet.clear(); console.log('\n--- Set after clearing ---'); console.log('Set size:', mySet.size); console.log('Is Set empty?', mySet.size === 0);

8. Date

A JavaScript date is represented internally as a single number, a timezone-agnostic value in milliseconds that has elapsed since the epoch, which is defined as the midnight at the beginning of January 1, 1970, UTC (equivalent to the UNIX epoch).

A timestamp needs to be interpreted as a structured date-and-time representation in two ways: as a local time determined by the host environment (user’s device) or as a Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), the global standard time defined by the World Time Standard.

-

The

getTimezoneOffset()method returns a date-specific difference in minutes between UTC and the host’s local time, accounting for variations like Daylight Saving Time.// To run Node.js script or shell with a specific timezone set via the environment variable, // prepend 'TZ=<IANA_TIMEZONE>' to the node command, for example `TZ=America/New_York node my.js`. // Get the system's resolved IANA timezone identifier using the Intl API. const tz = Intl.DateTimeFormat().resolvedOptions().timeZone; console.log(`System Timezone (Intl API): ${tz}`); // "America/New_York" // A date in winter (Standard Time in the Northern Hemisphere) const winterDate = new Date("2024-01-15T12:00:00"); // A date in summer (Daylight Saving Time in the Northern Hemisphere) const summerDate = new Date("2024-07-15T12:00:00"); console.log(winterDate.toString()); // Mon Jan 15 2024 12:00:00 GMT-0500 (Eastern Standard Time) console.log(`${winterDate.getTimezoneOffset() / 60} hours`); // 5 hours console.log(summerDate.toString()); // Mon Jul 15 2024 12:00:00 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time) console.log(`${summerDate.getTimezoneOffset() / 60} hours`); // 4 hours -

The JavaScript specification only specifies one format to be universally supported: the date time string format, a simplification of the ISO 8601 calendar date extended format:

YYYY-MM-DDTHH:mm:ss.sssZ.-

When the time zone offset is absent, date-only forms are interpreted as a UTC time and date-time forms are interpreted as a local time.

new Date('1975') // 1975-01-01T00:00:00.000Z new Date('1975-08') // 1975-08-01T00:00:00.000Z new Date('1975-08-19') // 1975-08-19T00:00:00.000Z new Date('1975-08-19T23:15') // 1975-08-20T03:15:00.000Z new Date('1975-08-19T23:15').toString() // Tue Aug 19 1975 23:15:00 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time) new Date('1975-08-19T23:15:30.000') // 1975-08-20T03:15:30.000Z new Date('1975-08-19T23:15:30.000').toString() // Tue Aug 19 1975 23:15:30 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time) -

The

toISOString()method returns a string representation of the date in the date time string format, with the time zone offset always set toZ(UTC).// toJSON() calls toISOString() and returns the result. const event = new Date("August 19, 1975 23:15:30 UTC"); console.log(JSON.stringify(event)) // "1975-08-19T23:15:30.000Z" console.log(event.toJSON()) // 1975-08-19T23:15:30.000Z -

The

toString()method returns a human-readable string representation of the date and time in the local timezone of the host environment.// Example output (depends on local timezone, e.g., America/New_York): const event = new Date("August 19, 1975 23:15:30 UTC"); console.log(event.toString()); // Tue Aug 19 1975 19:15:30 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time) -

The

toUTCString()method returns a string representation of the date and time in Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), which is typically based on RFC 7231.const event = new Date("August 19, 1975 23:15:30 UTC"); console.log(event.toUTCString()); // Tue, 19 Aug 1975 23:15:30 GMT -

Both

Date.parse()and theDate()constructor accept strings in the date time string format as input.const dateTimeString = '1975-08-19T23:15:30.000Z'; // Date.parse() returns a number (timestamp) Date.parse(dateTimeString) // 177722130000 new Date(177722130000) // 1975-08-19T23:15:30.000Z // new Date() constructor returns a Date object new Date(dateTimeString) // 1975-08-19T23:15:30.000Z

-

-

The

Dateobject can be instantiated in several ways, allowing for flexibility in representing specific moments in time.-

Date.now(): Returns the number of milliseconds elapsed since the epoch (January 1, 1970 00:00:00 UTC).console.log(`Date.now(): ${Date.now()}`); // Example output: Date.now(): 1721485200000 (this value changes every millisecond) -

new Date(): Creates a newDateobject representing the current date and time in the local timezone.const now = new Date(); console.log(`new Date(): ${now}`); // Example output: new Date(): Sat Jul 20 2024 10:30:00 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time) -

new Date(milliseconds): Creates a newDateobject representing the date and time corresponding to the given number of milliseconds since the epoch.const epochPlusMs = new Date(1721485200000); // Example timestamp console.log(`new Date(milliseconds): ${epochPlusMs}`); // Example output: new Date(milliseconds): Sat Jul 20 2024 10:20:00 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time) -

new Date(datestring): Creates a newDateobject by parsing the given date string.// ISO 8601-like strings are universally supported. const dateFromString = new Date("2024-07-20T10:30:00Z"); console.log(`new Date(datestring): ${dateFromString}`); // Example output: new Date(datestring): Sat Jul 20 2024 06:30:00 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time) -

new Date(year, month, date, hours, minutes, seconds, ms): Creates a newDateobject from individual date and time components.// Month is 0-indexed (0 for January, 6 for July, 11 for December). // All arguments are interpreted in the local timezone. const specificDate = new Date(2024, 6, 20, 10, 30, 0, 0); // July 20, 2024, 10:30:00 AM console.log(`new Date(year, month, ...): ${specificDate}`); // Example output: new Date(year, month, ...): Sat Jul 20 2024 10:30:00 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)When a segment overflows or underflows its expected range, it usually "carries over to" or "borrows from" the higher segment. For example, if the month is set to 12 (months are zero-based, so December is 11), it becomes the January of the next year. If the day of month is set to 0, it becomes the last day of the previous month.

new Date(1975, 12, -1).toString() // Tue Dec 30 1975 00:00:00 GMT-0500 (Eastern Standard Time)

-

9. JavaScript Object Notation (JSON)

JSON is a syntax for serializing objects, arrays, numbers, strings, booleans, and null, but undefined, NaN and Infinity are unsupported.

-

JSON.stringify()converts a JavaScript value into a JSON string, optionally transforming values or selecting properties using areplacerfunction or array, and formatting the output for readability with a specifiedspaceargument.-

Boolean,Number,String, andBigIntwrapper objects are converted to their corresponding primitive values during stringification, andSymbolobjects are treated as plain objects.BigInt.prototype.toJSON = function() { return this.toString(); }; // BigInt -> String const wrappers = { bool: new Boolean(true), num: new Number(42), str: new String("text"), big: Object(100n), sym: Object(Symbol("s")), }; JSON.stringify(wrappers) // {"bool":true,"num":42,"str":"text","big":"100","sym":{}} -

undefined,Function, andSymbolvalues are not valid JSON values, which will be either ommited in an object or converted tonullin an array.const obj = { a: "kept", b: undefined, c: () => {}, d: Symbol("s"), }; JSON.stringify(obj) // {"a":"kept"} const arr = ["kept", undefined, () => {}, Symbol("s")]; JSON.stringify(arr) // ["kept",null,null,null] -

The numbers

InfinityandNaN, as well as the valuenull, are all considerednull. -

BigIntvalues require a customtoJSON()method for serialization to avoid throwing aTypeError.try { JSON.stringify({ big: 100n }); } catch (error) { console.log(error.name); // "TypeError" } BigInt.prototype.toJSON = function () { return this.toString(); }; console.log(JSON.stringify({ big: 100n })); // {"big":"100"} -

Arrays are serialized into JSON arrays containing only their indexed elements, ignoring all other attached properties.

-

All

Symbol-keyed properties will be completely ignored, even when using thereplacerparameter. -

An object can define a

.toJSON(key)method to return a custom serializable value, allowing it to serialize itself differently based on its context (thekey, which is its property name, its string array index, or an empty string if serialized directly).const myObject = { toJSON: function (key) { return `I was serialized with key: "${key}"`; }, }; // 1. Serialized directly (key is an empty string) console.log(JSON.stringify(myObject)); // "I was serialized with key: \"\"" // 2. As a property in an object (key is the property name) const objContainer = { a_property: myObject }; console.log(JSON.stringify(objContainer)); // {"a_property":"I was serialized with key: \"a_property\""} // 3. In an array (key is the index as a string) const arrContainer = [myObject]; console.log(JSON.stringify(arrContainer)); // ["I was serialized with key: \"0\""] -

Only an object’s enumerable own properties can be serialized in a stable, predictable order which is why complex objects like

MapandSetbecome empty and require a customreplacerortoJSONmethod for proper serialization.const data = { metadata: new Map([["system", "prod"]]), }; const json = JSON.stringify(data, (key, value) => value instanceof Map ? Array.from(value.entries()) : value ); console.log(json); // {"metadata":[["system","prod"]]} -

The