TCP/IP: Introduction to TCP

So far we have been discussing protocols that do not include their own mechanisms for delivering data reliably.

-

They may detect that erroneous data has been received, using a mathematical function such as a checksum or CRC, but they do not try very hard to repair errors.

-

With IP and UDP, no error repair is done at all.

-

With Ethernet and other protocols based on it, the protocol provides some number of retries and then gives up if it cannot succeed.

The problem of communicating in environments where the communication medium may lose or alter the messages being delivered has been studied for years.

-

Some of the most important theoretical work on the topic was developed by Claude Shannon in 1948.

This work, which popularized the term bit and became the foundation of the field of information theory, helps us understand the fundamental limits on the amount of information that can be moved across an information channel that is lossy (that may delete or alter bits).

-

Information theory is closely related to the field of coding theory, which provides ways of encoding information so that it is as resilient as possible to errors in the communications channel.

Using error-correcting codes (basically, adding redundant bits so that the real information can be retrieved even if some bits are damaged) to correct communications problems is one very important method for handling errors.

-

Another is to simply "try sending again" until the information is finally received. This approach, called Automatic Repeat Request (ARQ), forms the basis for many communications protocols, including TCP.

1. ARQ and Retransmission

If we consider not only a single communication channel but the multihop cascade of several, we realize that not only may we have the types of errors mentioned so far (packet bit errors), but there may be others which might arise at an intermediate router and are the types of problems we brought up when discussing IP: packet reordering, packet duplication, and packet erasures (drops). An error-correcting protocol designed for use over a multihop communications channel (such as IP) must cope with all of these problems.

A straightforward method of dealing with packet drops (and bit errors) is to resend the packet until it is received properly. This requires a way to determine

-

(1) whether the receiver has received the packet and

-

(2) whether the packet it received was the same one the sender sent.

The method for a receiver to signal to a sender that it has received a packet is called an acknowledgment, or ACK. In its most basic form,

-

the sender sends a packet and awaits an ACK.

-

When the receiver receives the packet, it sends the ACK.

-

When the sender receives the ACK, it sends another packet, and the process continues.

Interesting questions to ask here are

-

(1) How long should the sender wait for an ACK?

Deciding how long to wait relates to how long the sender should expect to wait for an ACK.

-

(2) What if the ACK is lost?

If an ACK is dropped, the sender cannot readily distinguish this case from the case in which the original packet is dropped, so it simply sends the packet again.

Of course, the receiver may receive two or more copies in that case, so it must be prepared to handle that situation.

-

(3) What if the packet was received but had errors in it?

It is generally much easier to use codes to detect errors in a large packet (with high probability) using only a few bits than it is to correct them.

Simpler codes are typically not capable of correcting errors but are capable of detecting them. That is why checksums and CRCs are so popular.

In order to detect errors in a packet, then, we use a form of checksum.

When a receiver receives a packet containing an error, it refrains from sending an ACK. Eventually, the sender resends the packet, which ideally arrives undamaged.

Even with the simple scenario presented so far, there is the possibility that the receiver might receive duplicate copies of the packet being transferred. This problem is addressed using a sequence number.

-

Basically, every unique packet gets a new sequence number when it is sent at the source, and this sequence number is carried along in the packet itself.

-

The receiver can use this number to determine whether it has already seen the packet and if so, discard it.

The protocol described so far is reliable but not very efficient.

Consider what happens when the time to deliver even a small packet from sender to receiver (the delay or latency) is large (e.g., a second or two, which is not unusual for satellite links) and there are several packets to send.

-

The sender is able to inject a single packet into the communications path but then must stop until it hears the ACK. This protocol is therefore called "stop and wait".

-

Its throughput performance (data sent on the network per unit time) is proportional to M/R where M is the packet size and R is the round-trip time (RTT), assuming no packets are lost or irreparably damaged in transit.

-

For a fixed-size packet, as R goes up, the throughput goes down. If packets are lost or damaged, the situation is even worse: the "goodput" (useful amount of data transferred per unit time) can be considerably less than the throughput.

For a network that doesn’t damage or drop many packets, the cause for low throughput is usually that the network is not being kept busy. The situation is similar to using an assembly line where new work cannot enter the line until a complete product emerges. Most of the line goes idle. If we take this comparison one step further, it seems obvious that we would do better if we could have more than one work unit in the line at a time. It is the same for network communication—if we could have more than one packet in the network, we would keep it "more busy", leading to higher throughput.

Allowing more than one packet to be in the network at a time complicates matters considerably.

-

Now the sender must decide not only when to inject a packet into the network, but also how many.

-

It also must figure out how to keep the timers when waiting for ACKs, and it must keep a copy of each packet not yet acknowledged in case retransmissions are necessary.

-

The receiver needs to have a more sophisticated ACK mechanism: one that can distinguish which packets have been received and which have not.

-

The receiver may need a more sophisticated buffering (packet storage) mechanism—one that allows it to hold "out-of-sequence" packets (those packets that have arrived earlier than those expected because of loss or reordering), unless it simply wants to throw away such packets, which is very inefficient.

1.1. Windows of Packets and Sliding Windows

To handle all of these problems,

-

we begin with the assumption that each unique packet has a sequence number, as described earlier.

-

We define a window of packets as the collection of packets (or their sequence numbers) that have been injected by the sender but not yet completely acknowledged (i.e., the sender has not received an ACK for them).

We refer to the window size as the number of packets in the window.

-

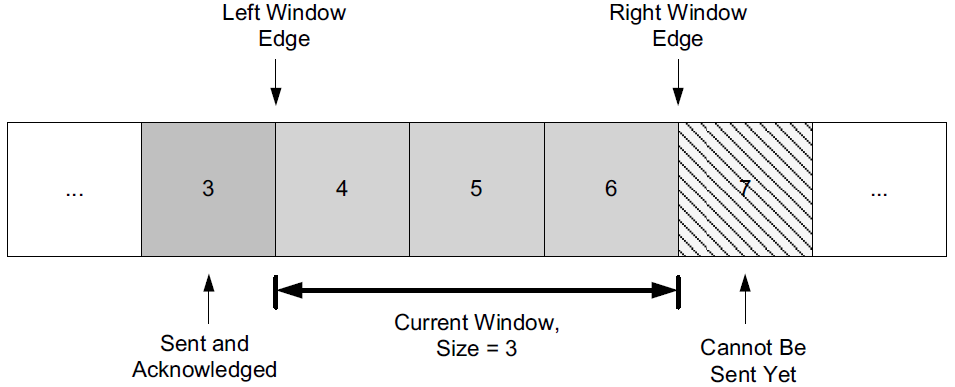

This figure shows the current window of three packets, for a total window size of 3.

-

Packet number 3 has already been sent and acknowledged, so the copy of it that the sender was keeping can now be released.

-

Packet 7 is ready at the sender but not yet able to be sent because it is not yet "in" the window.

-

If we now imagine that data starts to flow from the sender to the receiver and ACKs start to flow in the reverse direction, the sender might next receive an ACK for packet 4.

When this happens, the window "slides" to the right by one packet, meaning that the copy of packet 4 can be released and packet 7 can be sent.

This movement of the window gives rise to another name for this type of protocol, a sliding window protocol.

The sliding window approach can be used to combat many of the problems described so far. Typically, this window structure is kept at both the sender and the receiver.

-

At the sender, it keeps track of what packets can be released, what packets are awaiting ACKs, and what packets cannot yet be sent.

-

At the receiver, it keeps track of what packets have already been received and acknowledged, what packets are expected (and how much memory has been allocated to hold them), and which packets, even if received, will not be kept because of limited memory.

1.2. Variable Windows: Flow Control and Congestion Control

To handle the problem that arises when a receiver is too slow relative to a sender, we introduce a way to force the sender to slow down when the receiver cannot keep up. This is called flow control and is usually handled in one of two ways.

-

One way, called rate-based flow control, gives the sender a certain data rate allocation and ensures that data is never allowed to be sent at a rate that exceeds the allocation.

This type of flow control is most appropriate for streaming applications and can be used with broadcast and multicast delivery.

-

The other predominant form of flow control is called window-based flow control and is the most popular approach when sliding windows are being used.

In this approach, the window size is not fixed but is instead allowed to vary over time.

To achieve flow control using this technique, there must be a method for the receiver to signal the sender how large a window to use. This is typically called a window advertisement, or simply a window update. This value is used by the sender (i.e., the receiver of the window advertisement) to adjust its window size.

Logically, a window update is separate from the ACKs we discussed previously, but in practice the window update and ACK are carried in a single packet, meaning that the sender tends to adjust the size of its window at the same time it slides it to the right.

If we consider the effect of changing the window size at the sender, it becomes clear how this achieves flow control.

-

The sender is allowed to inject W packets into the network before it hears an ACK for any of them.

-

If the sender and receiver are sufficiently fast, and the network loses no packets and has an infinite capacity, this means that the transfer rate is proportional to (SW/R) bits/s, where W is the window size, S is the packet size in bits, and R is the RTT.

-

When the window advertisement from the receiver clamps the value of W at the sender, the sender’s overall rate can be limited so as to not overwhelm the receiver.

This approach works fine for protecting the receiver, but what about the network in between?

We may have routers with limited memory between the sender and the receiver that have to contend with slow network links. When this happens, it is possible for the sender’s rate to exceed a router’s ability to keep up, leading to packet loss. This is addressed with a special form of flow control called congestion control.

Congestion control involves the sender slowing down so as to not overwhelm the network between itself and the receiver.

-

Recall that in our discussion of flow control, we used a window advertisement to signal the sender to slow down for the receiver.

This is called explicit signaling, because there is a protocol field specifically used to inform the sender about what is happening.

-

Another option might be for the sender to guess that it needs to slow down.

Such an approach would involve implicit signaling—that is, it would involve deciding to slow down based on some other evidence.

1.3. Setting the Retransmission Timeout

One of the most important performance issues the designer of a retransmission based reliable protocol faces is how long to wait before concluding that a packet has been lost and should be resent.

Stated another way, What should the retransmission timeout be?

Intuitively, the amount of time the sender should wait before resending a packet is about the sum of the following times:

-

the time to send the packet,

-

the time for the receiver to process it and send an ACK,

-

the time for the ACK to travel back to the sender,

-

and the time for the sender to process the ACK.

Unfortunately, in practice, none of these times are known with certainty. To make matters worse, any or all of them vary over time as additional load is added to or removed from the end hosts or routers.

Because it is not practical for the user to tell the protocol implementation what the values of all the times are (or to keep them up-to-date) for all circumstances, a better strategy is to have the protocol implementation try to estimate them. This is called round-trip-time estimation and is a statistical process.

Basically , the true RTT is likely to be close to the sample mean of a collection of samples of RTTs. Note that this average naturally changes over time (it is not stationary), as the paths taken through the network may change.

Once some estimate of the RTT is made, the question of setting the actual timeout value, used to trigger retransmissions, remains.

-

If we recall the definition of a mean, it can never be the extreme value of a set of samples (unless they are all the same).

-

So, it would not be sensible to set the retransmission timer to be exactly equal to the mean estimator, as it is likely that many actual RTTs will be larger, thereby inducing unwanted retransmissions.

Clearly, the timeout should be set to something larger than the mean, but exactly what this relationship is (or even if the mean should be directly used) is not yet clear.

-

Setting the timeout too large is also undesirable, as this leads back to letting the network go idle, reducing throughput.

2. Introduction to TCP

Given the background we now have regarding the issues affecting reliable delivery in general, let us see how they play out in TCP and what type of service it provides to Internet applications.

2.1. The TCP Service Model

Even though TCP and UDP use the same network layer (IPv4 or IPv6), TCP provides a totally different service to the application layer from what UDP does.

TCP provides a connection-oriented, reliable, byte stream service.

-

The term connection-oriented means that the two applications using TCP must establish a TCP connection by contacting each other before they can exchange data.

-

The typical analogy is dialing a telephone number, waiting for the other party to answer the phone and saying "Hello", and then saying "Who’s calling?"

-

There are exactly two endpoints communicating with each other on a TCP connection; concepts such as broadcasting and multicasting are not applicable to TCP.

The TCP provides a byte stream abstraction to applications that use it.

-

The consequence of this design decision is that no record markers or message boundaries are automatically inserted by TCP. A record marker corresponds to an indication of an application’s write extent.

If the application on one end writes 10 bytes, followed by a write of 20 bytes, followed by a write of 50 bytes, the application at the other end of the connection cannot tell what size the individual writes were.

For example, the other end may read the 80 bytes in four reads of 20 bytes at a time or in some other way.

-

One end puts a stream of bytes into TCP, and the identical stream of bytes appears at the other end.

-

Each endpoint individually chooses its read and write sizes.

TCP does not interpret the contents of the bytes in the byte stream at all.

-

It has no idea if the data bytes being exchanged are binary data, ASCII characters, EBCDIC characters, or something else.

-

The interpretation of this byte stream is up to the applications on each end of the connection.

-

TCP does, however, support the urgent mechanism mentioned before, although it is no longer recommended for use.

2.2. Reliability in TCP

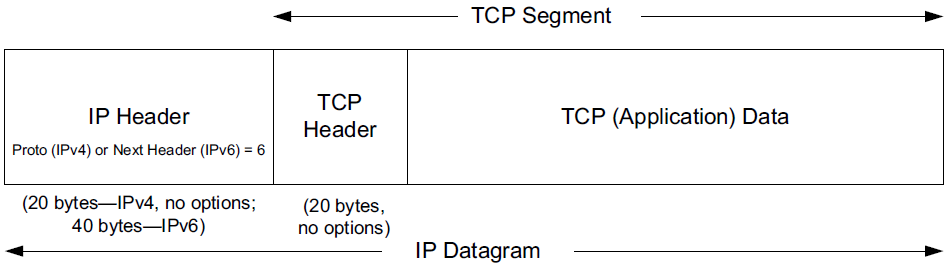

Because TCP provides a byte stream interface, it must convert a sending application’s stream of bytes into a set of packets that IP can carry. This is called packetization. These packets contain sequence numbers, which in TCP actually represent the byte offsets of the first byte in each packet in the overall data stream rather than packet numbers. This allows packets to be of variable size during a transfer and may also allow them to be combined, called repacketization.

The application data is broken into what TCP considers the best-size chunks to send, typically fitting each segment into a single IP-layer datagram that will not be fragmented. This is different from UDP, where each write by the application usually generates a UDP datagram of that size (plus headers). The chunk passed by TCP to IP is called a segment.

TCP maintains a mandatory checksum on its header, any associated application data, and fields from the IP header.

-

This is an end-to-end pseudo-header checksum whose purpose is to detect any bit errors introduced in transit.

-

If a segment arrives with an invalid checksum, TCP discards it without sending any acknowledgment for the discarded packet.

The receiving TCP might acknowledge a previous (already acknowledged) segment, however, to help the sender with its congestion control computations.

-

The TCP checksum uses the same mathematical function as is used by other Internet protocols (UDP, ICMP, etc.).

When TCP sends a group of segments, it normally sets a single retransmission timer, waiting for the other end to acknowledge reception.

-

TCP does not set a different retransmission timer for every segment.

-

Rather, it sets a timer when it sends a window of data and updates the timeout as ACKs arrive.

-

If an acknowledgment is not received in time, a segment is retransmitted.

When TCP receives data from the other end of the connection, it sends an acknowledgment.

-

This acknowledgment may not be sent immediately but is normally delayed a fraction of a second.

-

The ACKs used by TCP are cumulative in the sense that an ACK indicating byte number N implies that all bytes up to number N (but not including it) have already been received successfully.

This provides some robustness against ACK loss—if an ACK is lost, it is very likely that a subsequent ACK is sufficient to ACK the previous segments.

TCP provides a full-duplex service to the application layer.

-

This means that data can be flowing in each direction, independent of the other direction.

-

Therefore, each end of a connection must maintain a sequence number of the data flowing in each direction.

-

Once a connection is established, every TCP segment that contains data flowing in one direction of the connection also includes an ACK for segments flowing in the opposite direction.

-

Each segment also contains a window advertisement for implementing flow control in the opposite direction.

Thus, when a TCP segment arrives on a connection, the window may slide forward, the window size may change, and new data may have arrived.

Using sequence numbers, a receiving TCP discards duplicate segments and reorders segments that arrive out of order.

-

Recall that any of these anomalies can happen because TCP uses IP to deliver its segments, and IP does not provide duplicate elimination or guarantee correct ordering.

-

Because it is a byte stream protocol, however, TCP never delivers data to the receiving application out of order.

Thus, the receiving TCP may be forced to hold on to data with larger sequence numbers before giving it to an application until a missing lower-sequence-numbered segment (a "hole") is filled in.

Head-of-Line (HOL) blockingIn TCP, because it mandates in-order delivery, the receiver must hold onto subsequent packets until the missing "head-of-line" packet arrives out of order, blocking the delivery of all following packets.

In HTTP/1.1, because the connection-per-request limitation, even though the same connection could be reused, if the first request in a series is delayed, it will hinder the processing of subsequent requests. HTTP/2 addresses this by allowing multiple requests and responses to be interleaved over a single TCP connection, significantly reducing HOL blocking at the application layer.

3. TCP Header and Encapsulation

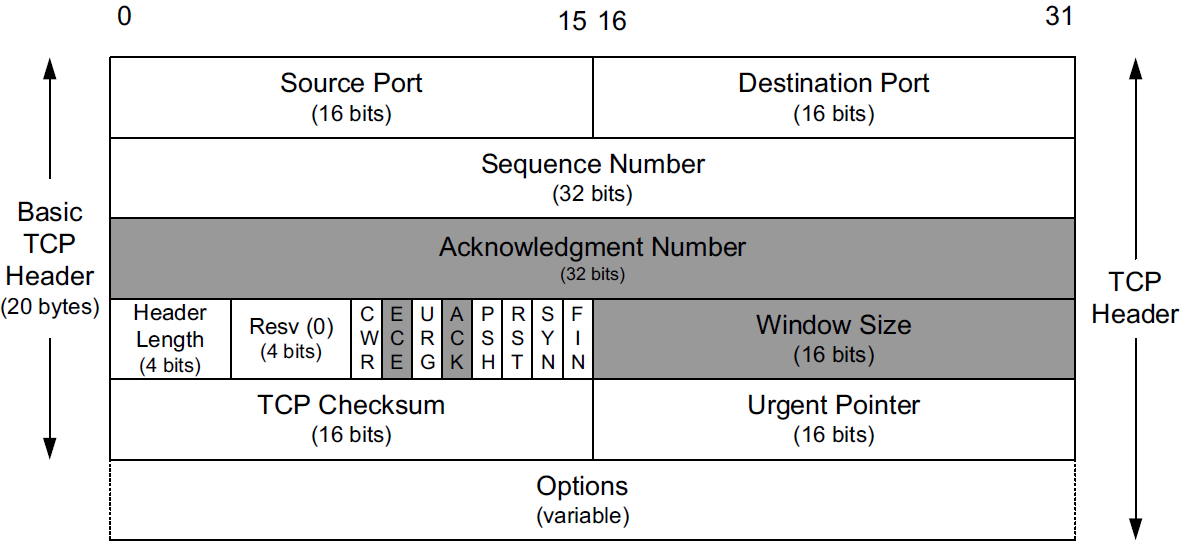

Each TCP header contains the source and destination port number.

-

These two values, along with the source and destination IP addresses in the IP header, uniquely identify each connection.

-

The combination of an IP address and a port number is sometimes called an endpoint or socket in the TCP literature.

The latter term appeared in [RFC0793] and was ultimately adopted as the name of the Berkeley-derived programming interface for network communications (now frequently called "Berkeley sockets").

It is a pair of sockets or endpoints (the 4-tuple consisting of the client IP address, client port number, server IP address, and server port number) that uniquely identifies each TCP connection.

The Sequence Number field identifies the byte in the stream of data from the sending TCP to the receiving TCP that the first byte of data in the containing segment represents.

Sequence number (32 bits)Has a dual role: [2]

If the SYN flag is set (1), then this is the initial sequence number. The sequence number of the actual first data byte and the acknowledged number in the corresponding ACK are then this sequence number plus 1.

If the SYN flag is clear (0), then this is the accumulated sequence number of the first data byte of this segment for the current session.

-

If we consider the stream of bytes flowing in one direction between two applications, TCP numbers each byte with a sequence number.

-

This sequence number is a 32-bit unsigned number that wraps back around to 0 after reaching (232) − 1.

-

Because every byte exchanged is numbered, the Acknowledgment Number field (also called the ACK Number or ACK field for short) contains the next sequence number that the sender of the acknowledgment expects to receive.

This is therefore the sequence number of the last successfully received byte of data plus 1.

This field is valid only if the ACK bit field is on, which it usually is for all but initial and closing segments.

-

Sending an ACK costs nothing more than sending any other TCP segment because the 32-bit ACK Number field is always part of the header, as is the ACK bit field.

When a new connection is being established, the SYN bit field is turned on in the first segment sent from client to server.

-

Such segments are called SYN segments, or simply SYNs.

-

The Sequence Number field then contains the first sequence number to be used on that direction of the connection for subsequent sequence numbers and in returning ACK numbers (recall that connections are all bidirectional).

Note that this number is not 0 or 1 but instead is another number, often randomly chosen, called the initial sequence number (ISN). The reason for the ISN not being 0 or 1 is a security measure.

-

The sequence number of the first byte of data sent on this direction of the connection is the ISN plus 1 because the SYN bit field consumes one sequence number.

-

Consuming a sequence number also implies reliable delivery using retransmission.

Thus, SYNs and application bytes (and FINs) are reliably delivered.

ACKs, which do not consume sequence numbers, are not.

TCP can be described as a sliding window protocol with cumulative positive acknowledgments.

-

The ACK Number field is constructed to indicate the largest byte received in order at the receiver (plus 1).

For example, if bytes 1–1024 are received OK, and the next segment contains bytes 2049–3072, the receiver cannot use the regular ACK Number field to signal the sender that it received this new segment.

-

Modern TCPs, however, have a selective acknowledgment (SACK) option that allows the receiver to indicate to the sender out-of-order data it has received correctly. When paired with a TCP sender capable of selective repeat, a significant performance benefit may be realized.

The Header Length field gives the length of the header in 32-bit words.

-

This is required because the length of the Options field is variable.

-

With a 4-bit field, TCP is limited to a 60-byte header.

-

Without options, however, the size is 20 bytes.

Currently eight bit fields are defined for the TCP header, although some older implementations understand only the last six of them.

-

CWR—Congestion Window Reduced (the sender reduced its sending rate);

-

ECE—ECN Echo (the sender received an earlier congestion notification);

-

URG—Urgent (the Urgent Pointer field is valid—rarely used);

-

ACK—Acknowledgment (the Acknowledgment Number field is valid—always on after a connection is established);

-

PSH—Push (the receiver should pass this data to the application as soon as possible—not reliably implemented or used);

-

RST—Reset the connection (connection abort, usually because of an error);

-

SYN—Synchronize sequence numbers to initiate a connection;

-

FIN—The sender of the segment is finished sending data to its peer;

TCP’s flow control is provided by each end advertising a window size using the Window Size field.

-

This is the number of bytes, starting with the one specified by the ACK number, that the receiver is willing to accept.

-

This is a 16-bit field, limiting the window to 65,535 bytes, and thereby limiting TCP’s throughput performance.

The Window Scale option that allows this value to be scaled, providing much larger windows and improved performance for high-speed and long-delay networks.

The TCP Checksum field covers the TCP header and data and some fields in the IP header, using a pseudo-header computation similar to the one used with ICMPv6 and UDP.

-

It is mandatory for this field to be calculated and stored by the sender, and then verified by the receiver.

-

The TCP checksum is calculated with the same algorithm as the IP, ICMP, and UDP ("Internet") checksums.

The Urgent Pointer field is valid only if the URG bit field is set.

-

This "pointer" is a positive offset that must be added to the Sequence Number field of the segment to yield the sequence number of the last byte of urgent data.

-

TCP’s urgent mechanism is a way for the sender to provide specially marked data to the other end.

The most common Option field is the Maximum Segment Size option, called the MSS.

-

Each end of a connection normally specifies this option on the first segment it sends (the ones with the SYN bit field set to establish the connection).

-

The MSS option specifies the maximum-size segment that the sender of the option is willing to receive in the reverse direction.

-

Other common options we investigate include SACK, Timestamp, and Window Scale.

$ sudo ethtool -K enp0s3 tx off rx off

$ sudo tcpdump -tnvS tcp and host blog.codefarm.me -i enp0s3

tcpdump: listening on enp0s3, link-type EN10MB (Ethernet), snapshot length 262144 bytes

IP (tos 0x0, ttl 64, id 46700, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 60)

192.168.71.40.54242 > 185.199.109.153.80: Flags [S], cksum 0x5b89 (correct), seq 3653972308, win 64240, options [mss 1460,sackOK,TS val 871608078 ecr 0,nop,wscale 7], length 0

IP (tos 0x0, ttl 50, id 0, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 60)

185.199.109.153.80 > 192.168.71.40.54242: Flags [S.], cksum 0xdc82 (correct), seq 4003978435, ack 3653972309, win 65535, options [mss 1380,sackOK,TS val 450401264 ecr 871608078,nop,wscale 9], length 0

IP (tos 0x0, ttl 64, id 46701, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 52)

192.168.71.40.54242 > 185.199.109.153.80: Flags [.], cksum 0x07b8 (correct), ack 4003978436, win 502, options [nop,nop,TS val 871608417 ecr 450401264], length 0

IP (tos 0x0, ttl 64, id 46702, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 133)

192.168.71.40.54242 > 185.199.109.153.80: Flags [P.], cksum 0xb144 (correct), seq 3653972309:3653972390, ack 4003978436, win 502, options [nop,nop,TS val 871608418 ecr 450401264], length 81: HTTP, length: 81

HEAD / HTTP/1.1

Host: blog.codefarm.me

User-Agent: curl/7.88.1

Accept: */*

IP (tos 0x0, ttl 50, id 12263, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 52)

185.199.109.153.80 > 192.168.71.40.54242: Flags [.], cksum 0x06ef (correct), ack 3653972390, win 279, options [nop,nop,TS val 450401606 ecr 871608418], length 0

IP (tos 0x0, ttl 50, id 12264, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 544)

185.199.109.153.80 > 192.168.71.40.54242: Flags [P.], cksum 0xde32 (correct), seq 4003978436:4003978928, ack 3653972390, win 279, options [nop,nop,TS val 450401607 ecr 871608418], length 492: HTTP, length: 492

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently

Connection: keep-alive

Content-Length: 162

Server: GitHub.com

Content-Type: text/html

Location: https://blog.codefarm.me/

X-GitHub-Request-Id: 449B:23A981:3B2944:3CBD56:675833E0

Accept-Ranges: bytes

Age: 488

Date: Tue, 10 Dec 2024 12:36:24 GMT

Via: 1.1 varnish

X-Served-By: cache-mel11268-MEL

X-Cache: HIT

X-Cache-Hits: 0

X-Timer: S1733834185.545813,VS0,VE1

Vary: Accept-Encoding

X-Fastly-Request-ID: 1c4484c44cb4e047ba4c0bd262516024cc90e8df

IP (tos 0x0, ttl 64, id 46703, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 52)

192.168.71.40.54242 > 185.199.109.153.80: Flags [.], cksum 0x0322 (correct), ack 4003978928, win 501, options [nop,nop,TS val 871608676 ecr 450401607], length 0

IP (tos 0x0, ttl 64, id 8458, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 60)

192.168.71.40.46328 > 185.199.109.153.443: Flags [S], cksum 0x3043 (correct), seq 3779096636, win 64240, options [mss 1460,sackOK,TS val 871608694 ecr 0,nop,wscale 7], length 0

IP (tos 0x0, ttl 64, id 8459, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 60)

192.168.71.40.46328 > 185.199.109.153.443: Flags [S], cksum 0x2c3a (correct), seq 3779096636, win 64240, options [mss 1460,sackOK,TS val 871609727 ecr 0,nop,wscale 7], length 0

IP (tos 0x0, ttl 50, id 0, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 60)

185.199.109.153.443 > 192.168.71.40.46328: Flags [S.], cksum 0x0f4e (correct), seq 1846548622, ack 3779096637, win 65535, options [mss 1380,sackOK,TS val 1063474721 ecr 871608694,nop,wscale 9], length 0

IP (tos 0x0, ttl 64, id 8460, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 52)

192.168.71.40.46328 > 185.199.109.153.443: Flags [.], cksum 0x36ec (correct), ack 1846548623, win 502, options [nop,nop,TS val 871609952 ecr 1063474721], length 0

IP (tos 0x0, ttl 64, id 8461, offset 0, flags [DF], proto TCP (6), length 569)

192.168.71.40.46328 > 185.199.109.153.443: Flags [P.], cksum 0xc22e (correct), seq 3779096637:3779097154, ack 1846548623, win 502, options [nop,nop,TS val 871609955 ecr 1063474721], length 517

...4. Summary

The problem of providing reliable communications over lossy communication channels has been studied for years. The two primary methods for dealing with errors include error-correcting codes and data retransmission. The protocols using retransmissions must also handle data loss, usually by setting a timer, and must also arrange some way for the receiver to signal the sender what it has received. Deciding how long to wait for an ACK can be tricky, as the appropriate time may change as network routing or load on the end systems varies. Modern protocols estimate the round-trip time and set the retransmission timer based on some function of these measurements.

Except for setting the retransmission timer, retransmission protocols are simple when only one packet may be in the network at one time, but they perform poorly for networks where the delay is high. To be more efficient, multiple packets must be injected into the network before an ACK is received. This approach is more efficient but also more complex. A typical approach to managing the complexity is to use sliding windows, whereby packets are marked with sequence numbers, and the window size bounds the number of such packets. When the window size varies based on either feedback from the receiver or other signals (such as dropped packets), both flow control and congestion control can be achieved.

TCP provides a reliable, connection-oriented, byte stream, transport-layer service built using many of these techniques. We looked briefly at all of the fields in the TCP header, noting that most of them are directly related to these abstract concepts in reliable delivery. TCP packetizes the application data into segments, sets a timeout anytime it sends data, acknowledges data received by the other end, reorders out-of-order data, discards duplicate data, provides end-to-end flow control, and calculates and verifies a mandatory end-to-end checksum. It is the most widely used protocol on the Internet. It is used by most of the popular applications, such as HTTP, SSH/TLS, NetBIOS (NBT—NetBIOS over TCP), Telnet, FTP, and electronic mail (SMTP). Many distributed file-sharing applications (e.g., BitTorrent, Shareaza) also use TCP.

References

-

[1] Kevin Fall, W. Stevens TCP/IP Illustrated: The Protocols, Volume 1. 2nd edition, Addison-Wesley Professional, 2011

-

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transmission_Control_Protocol#TCP_segment_structure